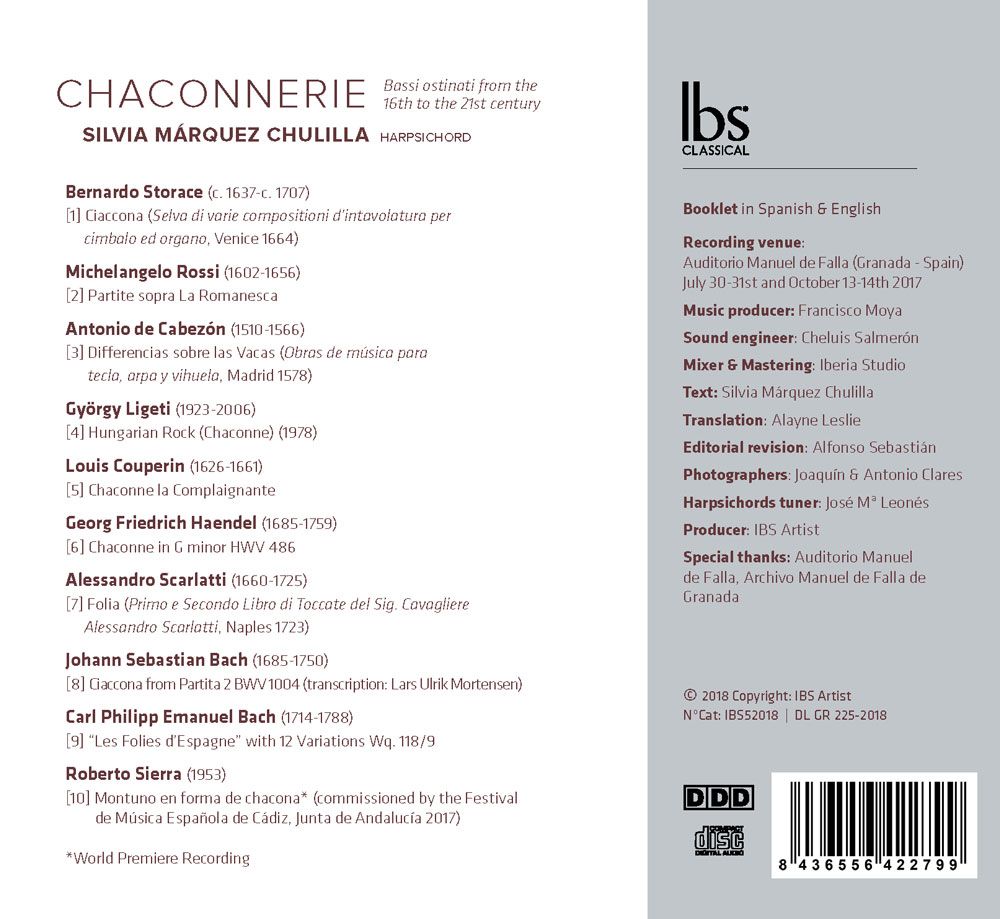

CHACONNERIE

BASSI OSTINATI FROM THE 16TH TO THE 21ST CENTURY

SILVIA MÁRQUEZ CHULILLA, clave

IBS CLASSICAL IBS52018 | DL GR 225-2018

Chaconnerie es un disco que habla de la repetición. Chaconnerie muestra ese principio del Arte que busca combinar elementos una y otra vez para alcanzar el equilibrio y la unidad. Chaconnerie invita a un viaje en el que los sonidos –a través de los siglos– se construyen sobre un esquema insistentemente repetido o fantasiosamente variado.

Incluye la primera grabación mundial del Montuno en forma de Chacona de Roberto Sierra, escrito para Silvia Márquez y nominado a los Latin Grammy Awards 2018.

CONTENIDO DEL CD

01 Ciaccona (Selva di varie compositioni d’intavolatura per cimbalo ed organo, Venezia 1664)

Michelangelo Rossi (1602-1656)

02 Partite sopra La Romanesca

Antonio de Cabezón (1510-1566)

03 Differencias sobre las Vacas (Obras de música para tecla, arpa y vihuela, Madrid 1578)

György Ligeti (1923-2006)

04 Hungarian Rock (Chaconne) (1978)

Louis Couperin (1626-1661)

05 Chaconne la Complaignante

Georg Friedrich Händel (1685-1759)

06 Chaconne in G minor HWV 486

Alessandro Scarlatti (1660-1725)

07 Folia (Primo e Secondo Libro di Toccate del Sig. Cavagliere Alessandro Scarlatti, Naples 1723)

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750)

08 Ciaccona from Partita 2 BWV 1004 (transcription: Lars Ulrik Mortensen)

Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach (1714-1788)

09 “Les Folies d’Espagne” with 12 Variations Wq. 118/9

Roberto Sierra (1953) *

10 Montuno en forma de chacona (commissioned by the Festival de Música Española de Cádiz, Junta de Andalucía 2017)

Bonus track oculto: Henry Purcell (1659-1695), A new Ground Z.T682 (Musick’s Hand-maid II, London 1689)

* World Premiere Recording

NOTAS AL CD

DE ALLENDE LOS MARES A LA EUROPA DEL SUR

Me gusta que las cosas sean exactamente lo mismo una y otra vez.

Andy Warhol

Chaconnerie es un disco que habla de la repetición. Chaconnerie muestra ese principio del Arte que busca combinar elementos una y otra vez para alcanzar el equilibrio y la unidad. Chaconnerie invita a un viaje en el que los sonidos –a través de los siglos– se construyen sobre un esquema insistentemente repetido o fantasiosamente variado.

La repetición inunda desde siempre las manifestaciones artísticas o expresiones del hombre, desde los moais de la isla de Pascua hasta los dibujos de Max C. Escher. La repetición es ritmo, pulso, vida. Y vida rezuma la chacona, danza a la que Lope de Vega atribuye origen americano («de las Indias a Sevilla/ha venido por la posta») y cuyo carácter describe Miguel de Cervantes como lascivo e inmoral. Con acento en el segundo tiempo y variación sobre esquema armónico, este bajo de danza –junto con los de zarabandas, folías y pasacalles– propició la improvisación sobre progresiones de acordes, novedad de gran impacto en el Barroco musical europeo.

En el hospital de Mesina (Sicilia), ciudad de la que partieron los barcos cristianos que ganaron la batalla de Lepanto en 1571, pasa algunos meses Miguel de Cervantes. La ciudad alcanza a principios del siglo XVII, bajo dominio español, su máximo esplendor y allí desarrolla su actividad Bernardo Storace (c. 1637-c. 1707). Poco más sabemos de él. Al otro extremo de la península, en Venecia, ve la luz en 1664 su Selva di varie compositioni d’intavolatura per cimbalo et organo, colección de variaciones sobre danzas y melodías populares junto con chaconas y pasacalles basadas en la repetición de cuatro compases. Hacia finales del siglo XVI y principios del XVII las fórmulas armónicas que se habían empleado en distintas danzas del Renacimiento –monica, españoleta, bergamasca, ruggiero, romanesca o folía– se utilizaron para la composición de series de variaciones.

La simplicidad transparente de la Ciaccona de Storace –construida sobre la forma primitiva del bajo de chacona– contrasta con la abstracción de las breves Partite sopra La Romanesca de Michelangelo Rossi (1602-1656). Nacido en Génova e instalado en Roma, fue reconocido por sus contemporáneos como excepcional violinista, pero su reputación reside en su obra para tecla, donde explora límites insospechados con los cromatismos. En las Partite esconde de tal modo el patrón original que el oyente realmente debe esforzarse para reconocer el bajo de Romanesca que, con ligeras variaciones, coincide en su fórmula melódico-rítmica con la española Guárdame las vacas.

Al servicio de los reyes más poderosos, Carlos V y Felipe II, Antonio de Cabezón (1510-1566) fue el organista y compositor más ilustre de la Europa del siglo XVI. Cultivó géneros sacros y seculares; entre estos últimos se cuentan «glosas» y «diferencias», que no son sino variaciones sobre un bajo ostinato y una melodía. Es el caso de las Differencias sobre las Vacas, escritas sobre un romance popular cuya letra evidencia que la picaresca estaba a la orden del día: «Guárdame las vacas, carillejo y besart’ he, sino, bésame tú a mi que yo te las guardaré».

ROMPER Y JUGAR CON LA TRADICIÓN

Conocí a György Ligeti (1923-2006) en un ambicioso encuentro dedicado a él y celebrado en La Haya en 1994. El objetivo era trabajar e interpretar toda su obra, y por suerte el clave no quedó fuera de juego. Su fuerte carácter no era sino espejo de la exigencia y el dominio en su campo creativo. Me sorprendió su tremenda admiración por la música antigua y su conocimiento de las músicas de Antonio de Cabezón, Michelangelo Rossi o Girolamo Frescobaldi. Había experimentado incluso con los temperamentos antiguos, llegando a concebir la Passacaglia Ungherese (1978) para un clave afinado en temperamento mesotónico (duro a los oídos actuales). Diez años antes su Continuum rompía abruptamente con todo lo escrito para clave hasta el momento: la paradójica creación de una ilusión de sonido continuo a partir de la repetición velocísima de notas –creando al mismo tiempo diferentes rítmicas y texturas– demuestra su conocimiento de la mecánica del instrumento y un brillante aprovechamiento de la resonancia del clave más allá del mundo tonal (con todo, no faltan referencias veladas al Clave bien temperado de J. S. Bach).

A la hora de abordar el Hungarian Rock (Chaconne) (1978) Ligeti reconocía, junto a la interválica y los ritmos balcánicos, la influencia del rock del momento y su tributo a los Beatles. En aquella ocasión no comprendí tal relación, más allá de los característicos acentos en el último tiempo del compás (el crash de la batería o el redoble de caja) que el compositor exigía sin haber escrito en la partitura, ya que «se daba por hecho» tratándose de un rock –una chacona, en definitiva, construida sobre cuatro compases–. Con el paso del tiempo me resulta innegable la influencia de canciones de la etapa más psicodélica de los Beatles: la rítmica de «Tomorrow Never Knows» (Revolver) o los efectos especiales de «A day in the life» (Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts) impregnan los escasos cinco minutos de Hungarian Rock.

Curiosamente, en una entrevista ofrecida a Ulrich Dibelius en 1993, György Ligeti reconocía que tanto Hungarian Rock como Passacaglia Ungherese habían sido concebidas como comentarios irónicos a las discusiones de sus alumnos en Hamburgo, y como reacciones al movimiento neotonal y postmoderno. La ironía, en cualquier caso, nos ha dejado una pieza clave en el repertorio del siglo XX y una obviedad: la tradición de la chacona sigue vigente hoy en día en la música de jazz, pop y rock.

DE LA CALLE A LA CORTE

Dirijamos por un momento nuestra mirada levemente al norte: el momento clave en la primera transformación de la chacona se da a principios del siglo XVII en la Francia de Luis XIV, donde pasa de ser danza social a los escenarios; la chacona la bailan las mujeres mientras que el pasacalle los hombres (Chorégraphie, ou L’art de décrire la dance, R.-A. Feuillet, 1703). De este modo, la primitiva forma binaria comenzó a hacerse más extensa (4, 5, 6 o más partes), como sucede en las obras de Lully, y poco después desembocaría en la forma rondó (A-B-A-C-A-D-A…). La Chaconne la Complaignante de Louis Couperin (1626-1661) es la perfecta ilustración de este nuevo género y el propio título (“la quejumbrosa”) sugiere un carácter bien distinto a aquella diversión suscitada por la danza original.

Del Manuscrito Bauyn se desprende que Couperin no organizaba sus piezas de clavecín con un orden fijo, sino que agrupaba los diferentes tipos de danza por tonalidades. Tras los preludios, allemandes, courantes, sarabandes… aparecían una o varias chaconas. El intérprete podía así seleccionar las piezas de una misma tonalidad para crear un conjunto de danzas a su gusto.

También como pieza aislada nos ha llegado, junto con otras danzas y en diversos manuscritos de la mano de sus copistas, la Chaconne en Sol menor HWV 486 de Georg Friedrich Händel (1685-1759). Son piezas tempranas, anteriores a su marcha a Inglaterra y probablemente de su época en Hamburgo (1702-1706), cuando se ganaba la vida en parte dando clases de clave. ¡Hamburgo! Allí conoció, sin duda, los claves del afamado constructor local Hieronymus Albrecht Hass, representante de la escuela alemana: instrumentos robustos, de sonido potente –lejos del brillo de los claves italianos y de la delicadeza de los franceses– y muy a menudo con un registro grave de 16’ cuya profundidad podemos comprobar en este caso en los últimos compases de la Chaconne.

Adoptando una vez más la nomenclatura francesa, Haendel nos presenta aquí otro tipo de transformación de la chacona: la forma tema y variaciones, práctica que muy posiblemente surgió de los propios músicos al tratar de huir de la monotonía que supone repetir de modo indefinido una estructura de cuatro/ocho compases.

GRANDES CICLOS DE VARIACIONES

Así, las variaciones instrumentales sobre un esquema armónico o una frase del bajo se convertirían en uno de los más grandes exponentes de la capacidad creativa de los compositores en el siglo XVIII.

En el universo de los bassi ostinati solo un nombre podía hacer sombra a la chacona: la folía, danza del siglo XV originaria de Portugal que posteriormente se trasladó a España. No podía recibir sino tal nombre (“locura”) una danza que se bailaba acompañada de cantos salvajes mientras los protagonistas parecían estar fuera de sí. El término pasó a designar un esquema armónico-melódico que ha resultado ser el más recurrente en la historia de la música y alcanzó su punto álgido alrededor de 1700 con las folías incluidas en el Opus V de Arcangelo Corelli.

El napolitano Alessandro Scarlatti (1660-1725) gozaba de gran fama como compositor de óperas y obras vocales. Sin embargo, quizás alentado por el éxito de Corelli y posteriormente del Op. 1 de Vivaldi (1705), escribe en 1710 un ciclo de treinta elaboradas variaciones sobre la folía, brillantes, vivas, virtuosas.

A casi dos mil kilómetros de distancia, en la fría Hamburgo, Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach (1714-1788) abandonaba en 1768 su puesto en la corte berlinesa de Federico de Prusia para suceder a su padrino G. Ph. Telemann como Kapellmeister. Carl Philipp había subrayado la importancia de la variación en el prefacio a sus Sechs Sonaten für Clavier mit veränderten Reprisen (Berlín, 1760): «Las repeticiones con variaciones son indispensables hoy en día. Todos esperan eso de cualquier intérprete».

Lo que quizás no podía esperarse es que en esas latitudes y en el último tercio del siglo XVIII la folía fuera un tema familiar para el viandante, sino más bien algo arcaico. Las doce variaciones sobre Les Folies d’Espagne Wq. 118/9 difuminan el carácter de danza para desplegar un abanico de fantasía, virtuosismo, caracteres contrastantes –teatrales, diría– y expresiones llevadas al extremo.

En todo caso –¡qué diantres!– abandonar el espíritu original es algo que ya había hecho su padre. Nada se aleja más de la lascivia, la locura y el desenfreno que la Ciaccona de la Partita n.º 2 BWV 1004 de Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750). Compuesta al parecer bajo el dolor de la noticia –a la vuelta de un viaje realizado en 1720– de la muerte de su esposa María Bárbara, la musicóloga Helga Thoene puso de relieve la retórica del lamento y los corales luteranos que se esconden a lo largo de la Ciaccona, lanzando mensajes morales y religiosos. «Si pudiera imaginarme a mí mismo escribiendo o concibiendo tal obra, estoy seguro de que la excitación extrema y la tensión emocional me volverían loco», confesaba Johannes Brahms.

Considerada una de las obras más profundas de la Historia de la música, la propia Ciaccona se convirtió en objeto de infinidad de arreglos y transcripciones desde el siglo XIX hasta nuestros días: para piano (Busoni, Brahms), órgano, violonchelo, guitarra, orquesta (Stokowski), etc. Tanta letra se ha vertido acerca del tema que únicamente quisiera destacar dos aspectos sobre la presente grabación.

Por una parte quiero hacer constar mi admiración por la transcripción de Lars Ulrik Mortensen. Clavecinista y director, profundo conocedor del instrumento, de la práctica del bajo continuo y del lenguaje contrapuntístico, publicó en 2003 esta magistral versión como epílogo a The Keyboard in Baroque Europe (Cambridge University Press), un conjunto de ensayos dedicados al desaparecido maestro Gustav Leonhardt en su 75º cumpleaños.

Por otra, la posibilidad de utilizar una copia del mayor clave conocido antes del siglo XX otorga a la Ciaccona una imponente dimensión organística. El clave original, construido por H. A. Hass en 1740 –con tres manuales, cinco juegos de cuerdas (16′ 8′ 8′ 4′ 2’), seis hileras de martinetes, un registro de laúd y otro de arpa para el 16’– acabó en manos del clavecinista Rafael Puyana. Este encargó posteriormente una copia a Robert Goble & Son, instrumento que donó al Archivo Manuel de Falla en Granada.

DE VUELTA AL CARIBE

Cerremos el círculo: crucemos de nuevo al otro lado del Atlántico. La irrupción de los Beatles en la década de los 60 coincide con la época de oro de la salsa en Puerto Rico. Y si György Ligeti incorpora a sus creaciones la música actual no menos lo hace Roberto Sierra (1953), que siempre ha desechado la falsa división entre música clásica y popular: «Soy puertorriqueño. Estoy representando los sonidos nuestros y del profundo Caribe». En absoluto es forzada la relación aquí traída entre Ligeti y Sierra, que reconoce al primero como su gran maestro desde sus estudios en Hamburgo: «La figura de Ligeti permanece en mi memoria tanto en el ámbito personal como artístico. Él fue amigo y mentor, ejemplo de absoluta integridad musical, y de aspiración a lo más depurado en términos de la técnica.»

A través de Ligeti conoció Roberto a Elisabeth Chojnacka, para quien escribió Con Salsa y Concierto Nocturnal (tuve el honor en 2011 de protagonizar su estreno en España, junto al Grupo Enigma, en el Auditorio de Zaragoza y en el Auditorio Nacional de Madrid). «Su gran presencia, virtuosismo y cualidades artísticas sin duda influyeron en mi acercamiento al clave.» Por ello no sorprende el dominio con el que aplica su lenguaje al instrumento en el Montuno en forma de chacona. Cuando en 2017 recibió el encargo por parte del Festival de Música Española de Cádiz no dudó en escribir un montuno, son de origen afrocubano: «Da la casualidad de que el uso de los ostinati es uno de mis recursos predilectos. El tener algo fijo que no cambia permite y obliga a la imaginación a desatar cadenas. En la composición contemporánea actúa como un ancla, como un sustituto a la falta de los centros tonales. Igualmente encaja perfectamente dentro de mis visiones caribeñas: las obstinadas repeticiones de los montunos en la música de salsa son pequeños pasacalles o chaconas.»

Como feliz dedicataria, me enfrento al poderoso ritmo del montuno, a la exigencia técnica y a la expresión de la locura (pequeño guiño a la folía incluido) que nos devuelve a la sensualidad del inicio, al origen de esas danzas ancladas a la tierra, a la vida y a la Naturaleza. Roberto escribe vitalidad, fantasía y locura. Bullicio, aire libre. Caribe.

EPÍLOGO CON TÉ INGLÉS

¿Podíamos olvidarnos de los ground basses y de Henry Purcell (1659-1695)? Apasionado de la variación, los bassi ostinati (grounds en Inglaterra) supondrían el sustento de algunas de sus más bellas piezas, tanto instrumentales como vocales. No hay más que recordar el sobrecogedor lamento «When I am laid in earth» («Cuando yazga en la tierra») de la ópera Dido y Eneas (1689).

No… volvamos a la Europa del XVII; recompongámonos, atusemos nuestros cabellos tras la furia puertorriqueña y relajemos el ambiente con A new ground, la versión instrumental del aria «Here the deities approve» perteneciente a la oda Welcome to all the pleasures (Bienvenidos todos los placeres).

Amable lector que has llegado hasta aquí, acepta mi invitación a esta pizca fugaz de elegante belleza mientras degustamos –¿por qué no?– un buen té inglés.

Silvia Márquez Chulilla