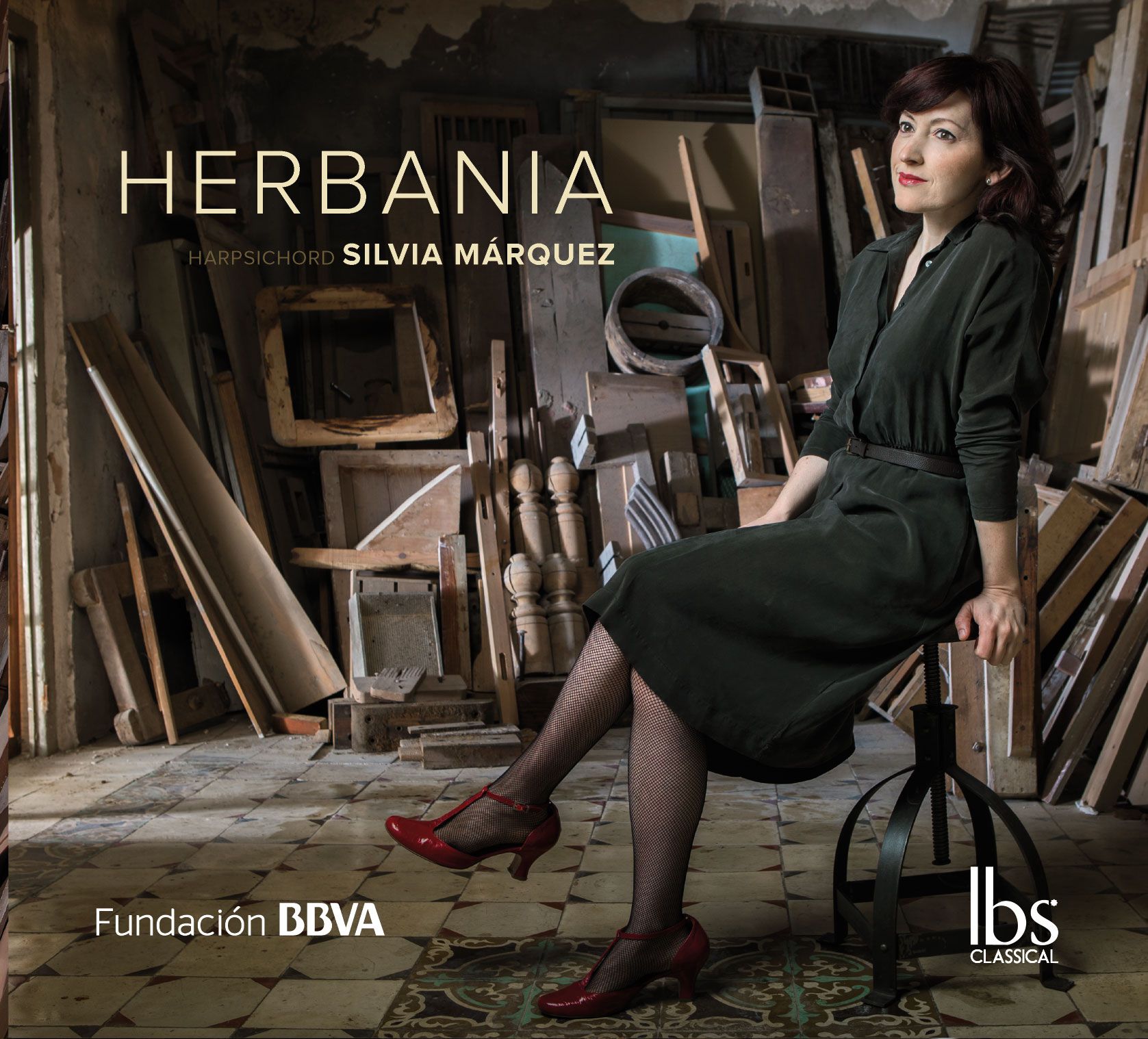

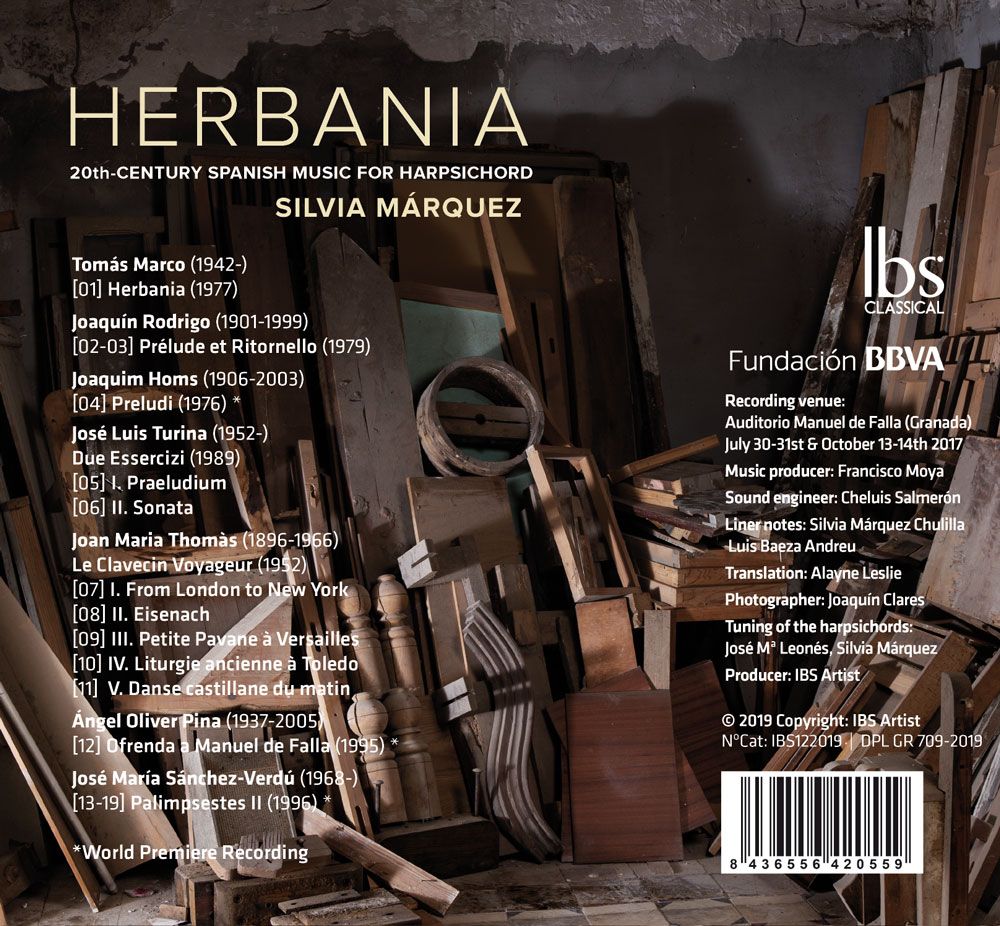

HERBANIA

20th-CENTURY SPANISH MUSIC FOR HARPSICHORD

SILVIA MÁRQUEZ CHULILLA, clave

IBS CLASSICAL IBS122019 | DL GR 709-2019

Siguiendo los pasos de su último y fascinante CD «Chaconnerie» –que incluye el Montuno de Roberto Sierra nominado a los Latin Grammy Awards–, la clavecinista Silvia Márquez Chulilla presenta aquí un sorprendente ramillete de piezas compuestas entre 1952 y 1996.

Tres primeras grabaciones mundiales –J. Homs, A. Oliver Pina, J. Mª Sánchez-Verdú– y tres de los compositores españoles más famosos del momento –Tomás Marco, José Luis Turina y el ya citado Sánchez-Verdú– invitan a adentrarse en el sonido punzante, metálico, rítmico, evocador, de la segunda mitad del siglo XX español.

CONTENIDO DEL CD

01 Herbania (1977)

Joaquín Rodrigo (1901-1999)

02-03 Prélude et Ritornello (1979)

Joaquim Homs (1906-2003)

04 Preludi (1976) *

José Luis Turina (1952-), Due Essercizi (1989)

05 I. Praeludium

06 II. Sonata

Joan Maria Thomàs (1896-1966), Le Clavecin Voyageur (1952)

07 I. From London to New York

08 II. Eisenach

09 III. Petite Pavane à Versailles

10 IV. Liturgie ancienne à Toledo

11 V. Danse castillane du matin

Ángel Oliver Pina (1937-2005)

12 Ofrenda a Manuel de Falla (1995) *

José María Sánchez-Verdú (1968-)

13-19 Palimpsestes II (1996) *

* World Premiere Recording

NOTAS AL CD

Cada uno debe caminar al paso de su propio tiempo. Dejemos que se creen nuevas bellezas y nos gustarán.

Wanda Landowska

Resulta imposible evitar ciertos trazos autobiográficos al introducir esta nueva colección de piezas no precisamente habituales: sonidos registrados en Granada, la ciudad que acogió en 1920 a Manuel de Falla y en la que éste recibió en 1922 la visita de la carismática Wanda Landowska. Gracias a este encuentro, Falla se convierte en el primer compositor del siglo XX que vuelve la vista al clave y lo introduce en una partitura orquestal – El retablo de Maese Pedro (1923)–. Su Concerto para clave y cinco instrumentos (1923-26), dedicado a Wanda, fue la primera pieza del siglo XX que entró en mi repertorio, siendo todavía estudiante en Zaragoza y poco consciente de lo que dicho concierto había supuesto en la Historia de la Música.

Mis posteriores estudios en Ámsterdam me introdujeron, de la mano de Annelie de Man, en el mundo de las partituras gráficas, las técnicas extendidas, la electrónica, el trabajo con los compositores; descubrí la figura de Antoinette Vischer y disfruté en vivo del ritmo cardíaco de los conciertos de Elisabeth Chojnacka. De la misma época data otro episodio situado en La Haya, en un encuentro dedicado al compositor György Ligeti, donde recuerdo con especial ilusión cómo un joven José María Sánchez-Verdú me entregaba Palimpsestes II; era la primera vez que un compositor me regalaba una obra para mi instrumento, dedicatoria incluida –aquí está, más de dos décadas después, cerrando el disco y grabada en primicia–.

¿Y qué había sido de la música para clave en España entre Falla y Sánchez-Verdú? A los ojos de una joven estudiante no era fácil responder cuando este repertorio no entraba en la formación reglada ni en la programación de las salas de conciertos. Nombres como Luis de Pablo o Tomás Marco aparecían rápidamente entre aquellos que habían escrito para A. Vischer o E. Chojnacka, pero más allá de esto el panorama no era muy alentador.

En uno de sus cuadernos de 1952, Wanda Landowska anotaba: «Me pregunto qué me puede traer la música moderna. ¿Será un refugio, una diversión, alegría, consuelo?». De 1952 data precisamente la pieza más antigua incluida en este CD: se trata de Le Clavecin Voyageur de Joan Maria Thomàs, organista y compositor que, adelantado de su época, había fundado en Mallorca en 1926 «l’Associació Bach per la música antiga i contemporània». Es quizás la primera pieza para clave compuesta en territorio español en el siglo XX tras las citadas de Manuel de Falla, a la sazón íntimo amigo del compositor mallorquín.

El primer impulso o acicate real para la creación tendrá lugar con la llegada de la clavecinista Genoveva Gálvez, primero a Santiago de Compostela en 1959 y más tarde, en 1972, a Madrid como primera catedrática de Clave de nuestro país. Genoveva irrumpe en la capital con mentalidad abierta, en contacto con los compositores del momento. Lo que ofrecerá esta España conservadora es una escritura en cierto modo convencional –ora como recreación de ambientes del pasado, ora a modo de homenaje– y que todavía no traspasa los límites del instrumento ni se adentra en la electrónica –en algunos casos rompedora en sonoridad, siendo los ejemplos más rebeldes los propios extremos del disco: Herbania y Palimpsestes–. A pesar de todo, el hecho de que un buen número de compositores preste atención al instrumento supone una ruptura, una renovación, la vuelta paulatina del clave al universo creativo contemporáneo. Genoveva será figura clave; no en vano tres de las piezas aquí recogidas están dedicadas a ella –las de Joaquín Rodrigo, José Luis Turina y mi paisano aragonés, Ángel Oliver–.

La Beca Leonardo de la Fundación BBVA, de la que fui beneficiaria en su edición de 2017, ha permitido hacer realidad no sólo este disco sino un amplio proyecto de divulgación de la música para clave en la España del siglo XX. El proyecto incluye un documental que verá la luz en un futuro próximo. De entre los compositores de este disco, aquellos que todavía están entre nosotros –así como la propia Genoveva– tuvieron la gentileza de recibirnos y compartir buena parte de su tiempo, sus primeros contactos con el clave, sus recuerdos…

En ocasiones nos afanamos en buscar sentido y explicaciones de más a las obras de arte. No hay mejor fortuna para el intérprete de hoy en día que contar con la presencia del compositor. Honestidad y sencillez brotan de las conversaciones con Tomás Marco, José Luis Turina, José María Sánchez-Verdú; virtudes que nos ayudan a normalizar y divulgar este repertorio, quizás también a actualizar su interpretación. Ellos no imponen límites, sugieren adaptar la música al instrumento y los registros disponibles. No hay grandes aspiraciones ni tribulaciones tras cada una de las obras: un momento, un descubrimiento, una idea… un pasado, una referencia y un timbre –que eventualmente atrae– con el que jugar. Desde el respeto al pasado, el clave lee nuevas páginas de tiempos cercanos.

Por eso no quería un folleto con unas notas técnicas, analíticas, enrevesadas –fechas y nombres acompañan a cada una de las pistas del CD; una rápida búsqueda en Internet arroja mucha más información sobre cualquiera de los compositores de lo aquí deseable–. Sí una mirada desde fuera, una escucha limpia, plasmada con la belleza e inquietud que destila la pluma de Luis Baeza. Con él os invito a adentraros en el sonido punzante, metálico, rítmico, evocador, de la segunda mitad del siglo XX español.

Silvia Márquez Chulilla

Distanciamiento con lo bello

Llamamos bello a lo extraño o quizás a lo misterioso e inaccesible. Nabokov dice que el ser humano, para reconocer lo hermoso, necesita mantener durante bastante tiempo un distanciamiento con ese objeto del deslumbramiento.

La rutina embrutece. Nos acostumbramos rápidamente a los protocolos del gesto y al de las palabras y ya no nombramos las cosas del mundo con ese fulgor intenso de lo primero. Y quizás por eso la fantasía de lo artístico, que nos obliga a sorprendernos y a extasiarnos, a mostrarnos fingidamente puros ante una creación que quede al margen del mundo pero que no puede existir sin él. Ser siempre, una y otra vez, algo distinto pero lo mismo. Regresar, de nuevo, para luego alejarse.

Éste es el periplo del clavicémbalo, un animal solemne que ha atravesado el tiempo y ha sido, a la vez, su testigo y portador. Aquí tenéis el tiempo, sentencia el clave. Nos lo trae en forma de adorno o con mayor simpleza. Lo representa con retorcimiento o con desgarro. Recoge de los palacios su atmósfera galante y de las islas de la vanguardia un viento temerario y aventurero. Tomad el tiempo, insiste, y a veces nos recuerda a un traje dorado o a un baile antiguo.

Clave femenina

Sus pasos se dirigieron pronto hacia un camino inexplorado de la mano de varias mujeres. Como quien intuye con claridad un destino, Wanda Landowska se adentró con determinación en ese bosque, todavía incierto, de las nuevas estéticas. Difusora e intérprete, además de rescatar al clavicémbalo para interpretar música barroca y clasicista, vio un medio expresivo idóneo para las novedosas manifestaciones contemporáneas. El oído ahora buscaría la sequedad y la contención en la expresión, lejos de aquellos arrebatos románticos y sentimentales de otras épocas. Un animal de fuerza mesurada, el clave; una especie que sedujo a su paso a grandes compositores como Falla y Poulenc.

Después de Landowska, otras mujeres consolidaron este regreso del clave a los escenarios y a la creación contemporánea. Muchos compositores del siglo XX escribieron con entusiasmo para Antoinette Vischer, Annelie de Man, Elisabeth Chojnacka o Goska Isphording. Y en España, en los años 60, fue Genoveva Gálvez, primera catedrática de clave, la que consiguió que aquella travesía inicialmente solitaria atrajera a los creadores del momento para poblar ese nuevo espacio de sonoridades sorprendentes.

Bocetos de atmósfera

La música nos organiza. Nos hace ser. Sonamos bajo la carne y las arterias. Una y otra vez. Siempre los mismos pero distintos. Retumba en la noche el dolor y se escucha la alegría siempre como un redoble de carcajadas.

Tiene este disco mucho de evocación primaria. Es una invitación a un viaje. Un acercamiento a algún lugar y una posterior huida, un desplazamiento hacia una ciudad o hacia una temperatura. Porque no solo se viaja a los puertos y a las plazas. Se aterriza, a menudo, en una atmósfera o en un recuerdo y son estas músicas las que nos traen al entendimiento sus formas más claras.

1. HERBANIA | Tomás Marco (1942-)

El paisaje es desértico y árido. La tierra volcánica es exuberante en su desnudez. Y el viento, la arena y las rocas, configuran en este espacio una cadencia peculiar gracias a sus desencuentros. Una ola. Otra. No producimos el ritmo: somos su antología. La angustia aparece como un estrechamiento en la garganta, los ojos cubiertos de arena y cardos. La pulsación de la música nos desenmascara. El primer bombeo, el primer vagido del idioma, el desplazamiento tectónico bajo la carne ya iniciado. Cantar es temblar. Somos cuerpos a la deriva, el acento sincopado en esta isla que no se acaba, el volcán dentro del volcán dentro del volcán.

2. 3. PRÉLUDE ET RITORNELLO | Joaquín Rodrigo (1901-1999)

La lentitud de una duda. Su persistencia. Ante la falta de certezas, se dan circunloquios y las palabras son un humo. Avanza la música morosa, decididamente irresoluble, de nuevo hacia su inicio. Tímidamente, se esconde y emerge. El canto es un círculo, la frustración de una historia que no encuentra su desembocadura. Y expectante, imperioso, espera un rayo de luz para acabar con esa cobardía.

Liberado ya de su claustrofobia, encuentra, al fin, el canto su cauce. Y lo que antes andaba a tientas, ahora se desenvuelve con obsesiva firmeza hacia una conclusión desde hace tiempo necesitada.

4. PRELUDI | Joaquim Homs (1906-2003)

La realidad queda lejos: el río, en el propio río; la lágrima, al borde del ojo, en alguna vergonzosa cama; la tormenta, en su propio desastre. Lo humano es una mancha. Los sonidos se contemplan en un espejo y se reconocen puros, autosuficientes. El universo de doce esferas se mueve en rotación constante y todos los cuerpos son reflejo de sí mismos o de otros cuerpos. Y el mundo juega a ser esta melodía acelerada a través de imágenes rotas, fragmentarias. La música supone un placer íntimo y absoluto. Será en el cuerpo desnudo de la poesía, desposeído ya para siempre de ropajes, puro e inocente como quiso Juan Ramón, donde nos reuniremos para celebrar el ritual del arte.

5. 6. DUE ESSERCIZI | José Luis Turina (1952-)

PRAELUDIUM | El intérprete despliega los acordes como una incertidumbre, a la manera de los preludios non mesurés de Louis Couperin. La melodía será una expectativa, un deseo suspendido a la espera de su resolución más plausible. O de su continuidad más lógica. Es un juego de voluntades: el intérprete agrupa las notas sin medida, como un artesano que da forma a la materia, y el oyente se ofrece como un destino al que irá a morir ese nuevo ser de aire.

SONATA | La conmoción vendrá después por la ráfaga imparable de las semicorcheas. Vivas e insistentes, no darán tregua al silencio. Y la música será perpetua como un remordimiento. Miguel de Unamuno manifestó su sed de eternidad, el secreto y pudoroso anhelo de los hombres de existir para siempre. La muerte quizás sea tan solo un artificio ortográfico que da sentido. Necesitamos de los finales cuando ya se han agotado todas las posibles combinaciones. Como dice Borges, el final producirá, ante todo, un gran alivio.

7. 8. 9. 10. 11. LE CLAVECIN VOYAGEUR | Joan María Thomás (1896-1966)

I. FROM LONDON TO NEW YORK | En las grandes ciudades conviven el cieno y la esperanza. La velocidad de la luz no es mayor que la de los cuerpos. Se amontona la gente frenética y torpe, como palomas desorientadas que no lucirán nunca su vuelo. Se deambula hacia lugares inciertos, pero siempre con la determinación del que viaja a un destino. Se huye. Es fácil disimular la pena en el centro de esta hipérbole. Y la euforia y la alegría apenas quedan dibujadas. Nadie reparará en ese cuerpo multiplicado. Y avanzarán las horas atropellándose, atravesando el ánimo del que escapa una procesión de máquinas. Y la ciudad será un sabor de hierro en los labios y una temperatura inaudita en la sangre.

II. EISENACH | Regresar a esta ciudad es darle coherencia al relato. Se ordena la sintaxis de los recuerdos y la mente entiende, por fin, su idioma. Seguirá estando el castillo, la fuente y el camino empedrado. La luz dolorosa de la tarde será idéntica. Otra vez la ilusión de lo repetido. Hay ciudades que tienen una ortografía complicada, una densidad de fuga o de ventolera. Está grabado en ti el artificio de una música antigua y, al contemplar las torres, los puentes, la almena, la misma bandada de pájaros de entonces te refrescará en la memoria su melodía afectada.

III. PETITE PAVANE À VERSAILLES | Las muñecas han desarrollado una sorprendente disposición para la eternidad. En su palacio de lámparas de araña, bailan una danza ortopédica. Son larguísimos los pasillos y aún más infinitas sus sonrisas. Te asomas a la vieja casa con inquietud. La felicidad fue un trozo de plástico; la niñez, esta danza mutilada en donde se desangra el tiempo con su mejor traje.

IV. LITURGIE ANCIENNE À TOLEDO | El viaje es siempre una pregunta. Y en éste asciendes por las calles con un ánimo interrogativo. A veces, un laberinto. Llegas al vientre de otro siglo y la armonía suena como la lanza de un lánguido caballero. El aire trae el recuerdo de alguna batalla, el berreo estrepitoso de los animales que enloquecieron en la plaza, el enigma de las brujas que cruzaron la noche con sus mejunjes para los enamorados. Un rey sabio traduce con su corte lo que se sabe del movimiento de los astros. Se conjugan los verbos y las constelaciones, los objetos de los sentidos y los del alma. Miran todos aquellos hombres al cielo, y allí se confían, aferrados a un idioma fabuloso al que ya le están creciendo los huesos.

V. DANSE CASTILLANE DU MATIN | En la plaza, los niños juegan bajo el sol. Ese bostezo de luz produce junto con la aridez de algunas tristezas un contrapunto. La fuente, en el centro, expulsa una respiración fatigada. Allí se amontonan los más pequeños con ansiedad y los pájaros descansan de su ilusión del vuelo. Transcurre el tiempo boca arriba y ruge, desde la lejanía, el estómago de algún gigante. Se suceden valerosos los días, y permanecen leales la plaza, el camino, la eterna llanura, la alegría de los bailes antiguos que laten todavía bajo la piel desmemoriada de algún andante caballero.

12. OFRENDA A MANUEL DE FALLA | Ángel Oliver Pina (1937-2005)

Nos traerán las flores un olor a sexo. Se añorará la tibieza de aquella saliva enamorada. Y del fondo de la garganta, emergerá rota una queja y un misterio. Desplegará la mañana su herida y temblará en el agua el deseo. La música será el embrujo, el alimento de este incendio.

Bajo la carne hay una violencia que perforará la tierra: algunas ciudades duelen tanto como un tajo.

13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. PALIMPSESTES | José María Sánchez-Verdú (1968-)

Ni siquiera una ola rompe dos veces igual. Cada tristeza nueva tiene su forma. Y los labios entusiasmados pronunciarán siempre de forma diferente las mismas palabras del amor. Caeremos por las mismas razones, pero el daño será siempre desigual.

El arte vuelve siempre sobre sí, pero nunca idéntico, como el río de Heráclito. La música y la literatura siempre han partido, en realidad, de otras obras engendradoras. Y la novedad y la innovación son, en este sentido, solo una fantasía.

A modo de palimpsestos, se superponen los motivos, se travisten, se modifican. Y el resultado será un pastiche o una parodia, una prolongación o un desarrollo, una construcción que se levanta sobre el Tiento de primer tono de Antonio de Cabezón. Desde ahí, el nuevo ser, ejemplar vibrante y antiguo, respira a través de estos siete palimpsestos, siete poderosos pulmones, hecho de sí mismo una y otra vez, superado desde su propia genética vigorosa y renovada.

Luis Baeza Andreu