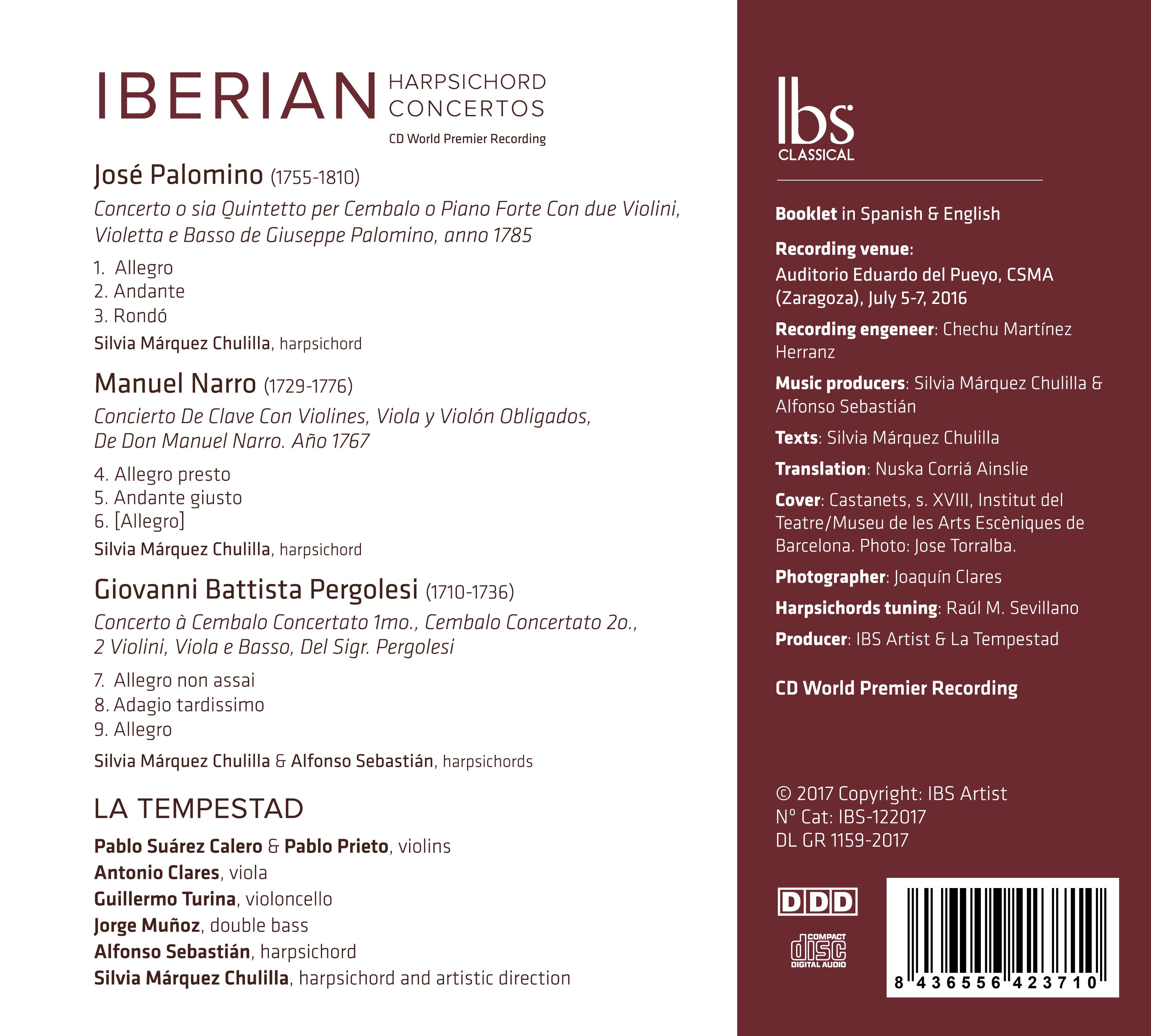

IBERIAN

HARPSICHORD CONCERTOS

LA TEMPESTAD | SILVIA MÁRQUEZ & ALFONSO SEBASTIÁN, claves

IBS CLASSICAL IBS122017 | DL GR 1159-2017

Iberian Harpsichord Concertos rinde homenaje al fenómeno dieciochesco que supuso el concierto para tecla y que tuvo en Giovanni Battista Pergolesi, Manuel Narro y José Palomino a tres portentosos representantes de este acontecimiento musical en el Sur de Europa. «Desde el brillo del temprano virtuosismo italiano, que tantísimos lazos cruzó con España y Portugal, al baile popular dieciochesco, el color del sur, los ecos de la guitarra rasgueada o la influencia de la escritura scarlattiana nos llevan a unos conciertos frescos, despreocupados, crujientes.»

Este registro constituye la primera grabación mundial en CD de los conciertos de Narro (primer concierto español para clave y orquesta) y Pergolesi, así como la primera al clave del Concerto de Palomino.

CONTENIDO DEL CD

1. Allegro

2. Andante

3. Rondó. Allº. poco

Silvia Márquez Chulilla, harpsichord

Manuel Narro (1729-1776), Concierto De Clave Con Violines, Viola y Violón Obligados, De Don Manuel Narro. Año 1767

4. Allegro presto

5. Andante giusto

6. [Allegro]

Silvia Márquez Chulilla, harpsichord

Giovanni Battista Pergolesi (1710-1736), Concerto à Cembalo Concertato 1mo., Cembalo Concertato 2o., 2 Violini, Viola e Basso, Del Sigr. Pergolesi

7. Allegro non assai

8. Adagio Tardissimo

9. Allegro

Silvia Márquez Chulilla & Alfonso Sebastián, harpsichords

CD World Premiere Recording

NOTAS AL CD

ENTRE JÁCARAS Y BOLEROS

En cierta ocasión estuvo en su casa, a la cuesta del mes de agosto, un padrecito de estos atusados, con un poco de copete en el frontispicio, cuellierguido, barbirrubio, de hábito limpio y plegado, zapato chusco, calzón de ante, y gran cantador de jácaras a la guitarrilla, del cual no se apartaba un punto nuestro Gerundico, porque le daba confites. Tenía el buen padre, mitad por mitad, tanto de presumido como de evaposado.

José Francisco de Isla (Historia del famoso predicador fray Gerundio de Campazas, alias Zotes, 1758)

Los archivos catedralicios, poderosos guardianes del arte musical de cada época, nos han permitido conocer una ingente cantidad de música religiosa de la España del XVIII y también atesoran la música instrumental de los más afamados compositores europeos del momento. Pero el cuadro queda incompleto y descolorido si no podemos imaginar el papel de la música en la vida cotidiana, la relación del clero con el mundo terrenal, su convivencia con los bailes y costumbres populares. La literatura es, muy a menudo, el camino que nos traslada a aquellos ambientes. Y el “padrecito” cantador de jácaras que nos presenta José Francisco de Isla no es sino una crítica descarnada al clero basada en la sátira y la ironía, pero que se aferra a la novela moderna y a su compromiso con la realidad; tanto, que la Inquisición censura el libro a los veinte días de su aparición y en 1762 un decreto prohíbe a Isla publicar cualquier obra nueva.

Una censura tan rápida y tajante, que como hecho aislado podría resultar comprensible tratándose de un ataque directo, sorprende si tenemos en cuenta el contexto sociocultural y los tremendos cambios que estaban teniendo lugar: frente a los tradicionalistas, el pensamiento ilustrado y la razón tenían un gran defensor en la figura de Carlos III; se reivindicaba la educación y el conocimiento como herramientas para conseguir el progreso y la felicidad; en 1759 comienza a editarse la Encyclopedie; se crean numerosas Academias y se produce un curioso fenómeno cultural: en oposición al grupo de los ilustrados –hombres cultivados y afines a los gustos franceses– aparece el “majismo”, representado por la mayoría del pueblo y aferrado a lo castizo; llamaban petimetre y currutaco a todo lo foráneo y acompañaban sus bailes –fandangos, boleros y seguidillas– con guitarras, laúdes y castañuelas. Los límites entre ambos grupos comenzaron a difuminarse cuando la propia aristocracia empezó a adoptar costumbres plebeyas o a mostrar a los visitantes la gracia de los bailes populares. Bajo el reinado de Carlos III, Francisco de Goya trabajó para la Real Fábrica de Tapices: el espíritu ilustrado fomentaba la industria de calidad, pero la temática representaba el pintoresquismo, los bailes y las diversiones populares. En las postrimerías del siglo, el escritor y político ilustrado Gaspar Melchor de Jovellanos retrata en su Diario la convivencia de todos estos elementos en una jornada cotidiana:

Domingo, 23 [de julio] (1797). En pie a las cinco. Sol claro. Misa, y a caballo a las seis y media. Nubes. A Caldones, convidado del indiano don Alonso Acebal, a su fiesta del Carmen; allá, un lector de teología de Salamanca, cisterciense, y la familia de Fano, de Quintana; varios curas de la redonda, y la parentela de casa; de Gijón, don Eduardo y el escribano Misericordia. A la Iglesia; la romería, en una hermosa carbayeda junto a ella, sin campo; quitada la tierra por Rato para una heredad, de que se resienten bien los árboles, que son bellos, pero están tristes y mal alimentados; poca gente; la comida, en un prado; ochenta personas; lo de costumbre, sin exceso en cantidad ni en modo. Tarde, a la iglesia; mal camino, y mucho; el sol nos incomoda; dos gaiteros, un tambor de Gijón, cuatro tiradores; más romería; algunas danzas. Vi a la Marica Ramírez mañana y tarde. ¡Cuál!

Gaspar Melchor de Jovellanos (Diario, 1790-1801)

Es este rico mosaico del último tercio de siglo que nos describen Isla y Jovellanos el que enmarca la composición de los conciertos de Manuel Narro y José Palomino, un género que pese a su importante desarrollo en Europa apenas tuvo representación aquí, al compás de tanta música religiosa, jácara y bolero.

CONCIERTOS PARA CLAVE, ÓRGANO O FORTE E PIANO

El concierto para tecla es un afortunado suceso dieciochesco, siglo en el que paulatinamente los compositores descubren el asombroso potencial armónico y polifónico de estos instrumentos más allá de su función de soporte desde el bajo continuo. El quinto Concierto de Brandemburgo de J. S. Bach (años 20 del siglo XVIII), los posteriores BWV 1052-1065, los Conciertos para Órgano de Georg Friedrich Haendel (1738) y los de Thomas Arne para clave, órgano o forte e piano (1751) son ejemplos representativos de un género que alcanzó su apogeo en la segunda mitad de siglo. Para Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach el concierto de tecla fue una constante a lo largo de toda su vida, desde que comenzó a escribir los primeros en 1733 hasta el Concierto en Mib Wq. 47 para clave y fortepiano de 1788. En el ámbito ibérico, el Concierto en La mayor del portugués Carlos Seixas (1704-1742) y otro en Sol menor atribuido al mismo autor son casos tempranos y aislados. Más adelante destacan los Quintetti Op. 56 y 57 de Luigi Boccherini –que llegó a España en 1768– y los Seis quintetos para instrumentos de arco y Órgano o clave obligado de Antonio Soler, fechados en 1776.

Atribuido a Giovanni Battista Pergolesi (1710-1736) y conservado en un manuscrito de la Universidad de Michigan, el Concerto à Cembalo Concertato 1mo., Cembalo Concertato 2o., 2 Violini, Viola e Basso P 240 III constituye el primer ejemplo conocido de este tipo –concierto para dos claves con orquesta– en el sur de Europa. Nápoles, territorio bajo mandato español desde 1504 hasta 1707, era en el siglo XVIII la ciudad más poblada de Italia. La producción de ópera en manos de compositores como Alessandro Scarlatti la convirtió en un centro cosmopolita, y sería cuna o centro de partida de muchos de los músicos que más tarde trabajaron en las cortes de Madrid y Lisboa (sin ir más lejos, Domenico Scarlatti).

En esa populosa Nápoles concurrida por comerciantes, taberneros, aristócratas, mendigos, hilanderas… –personajes tan bien representados en los famosos belenes napolitanos– Giovanni Battista Pergolesi trabaja desde 1725, en el entorno de la Corte, al servicio de diversos aristócratas. Con una importante producción operística –no podía ser de otro modo–, pronto se hizo famoso como representante de la opera buffa (La Serva Padrona), aunque también escribió obras sacras (Stabat Mater) e instrumentales (entre ellas un concierto de violín). El Concerto para dos claves, de escritura plenamente barroca y claramente construido sobre una línea de bajo continuo, transmite desde luego en sus tres movimientos la imagen de un entorno rico, alegre, bullicioso y ávido de ocio. Si damos por cierta su autoría y teniendo en cuenta que Pergolesi murió muy joven en 1736, el concierto sería estrictamente contemporáneo de los Conciertos para dos claves de J. S. Bach –BWV 1060 y 1061–, si no anterior.

Pero… ¿a quién iban dirigidos estos conciertos?, ¿dónde se interpretaban? Del entorno centroeuropeo nos llegan multitud de datos: Bach, director del Collegium Musicum de Leipzig entre 1729 y 1741, escribía muchos de sus conciertos para las sesiones del Café Zimmermann, donde eran estrenados por sus hijos (C. P. E. Bach o W. Friedemann) o alumnos aventajados. En Londres, un nuevo concierto escrito e interpretado en el intermedio por Haendel o Arne servía como reclamo a diversos oratorios. Las últimas composiciones del género de C. P. E. Bach nutrían las series de conciertos que dirigía en Hamburgo. Poco se conoce todavía, sin embargo, de esos conciertos de pago en España, y los repertorios que amenizaban las veladas musicales de la Casa de Benavente u Osuna parecían inclinarse hacia la música de ópera y de cuerda. Soler –discípulo en Madrid de Domenico Scarlatti y de José de Nebra– escribió los Quintetos para su pupilo el Infante D. Gabriel, hijo de Carlos III.

En aquella España ilustrada de Carlos III, la misma que en 1760 prohibía la publicación de Fray Gerundio…, un sacerdote valenciano que dedica su quehacer cotidiano al servicio litúrgico escribe en 1767 la que quizás sea su obra más castiza, atrevida, entretenida, costumbrista; una obra instrumental para la que no se conoce destinatario ni ocasión de estreno: el “Concierto De Clave Con Violines, Viola y Violón Obligados”. Se trata, si repasamos los antecedentes expuestos más arriba, del primer concierto español para clave conocido hasta la fecha.

Nacido en Valencia en 1729, Manuel Narro se ordenó sacerdote en la Colegiata de Játiva y allí fue organista entre 1752 y 1771, con un breve periodo en medio durante el que ocupó el mismo puesto en la Catedral de Valencia. En 1768, tras la muerte de José de Nebra, opositó a la cuarta plaza de organista de la Real Capilla de Madrid. A pesar de que el tribunal lo calificó como el mejor, la vacante fue adjudicada al joven José Lidón. Sin embargo, en 1771 Narro renuncia a su puesto en Játiva y aparece como organista de las Descalzas Reales de Madrid. Allí permanece hasta 1775, año en que vuelve a Valencia, ciudad donde fallece en 1776. La difusión que alcanzó su música (con copias en lugares tan diversos como Cuenca, Madrid, Salamanca, Valencia, México…) evidencia el reconocimiento del que gozaba como compositor. Frente a sus más de 60 obras vocales religiosas (misas, motetes, villancicos, himnos, etc.), la producción instrumental conocida es escasísima: tres obras para tecla y el Concierto de Clave, del que se conserva una copia en la Colegiata de Roncesvalles. Al parecer, tras finalizar la oposición a la Catedral de Valencia, los examinadores consideraron que Narro tañía “con más propiedad y más conforme para la Iglesia” que el otro ganador, Rafael Anglés, más “moderno”. A pesar de los escasos datos biográficos, no nos resulta difícil imaginar que Narro pudiera conocer la obra para tecla de Domenico Scarlatti, bien en su entorno madrileño, bien de mano de alguno de sus amigos valencianos en la Corte. Lo que sí es claro, sin embargo, es la influencia de aquél en el Concierto, de estética galante, alejado del estilo eclesiástico y rebosante de brillo con sus acordes rítmicos, acciacaturas, disonancias melódicas, giros ornamentales y cruces de manos.

Tan sólo unos meses antes de que Narro se trasladara a Madrid, el joven José Palomino –hijo de Francisco Mariano, un violinista zaragozano que trabajaba en los teatros madrileños– obtenía plaza como violinista en la Real Capilla. Ambos debieron de vivir muy cerca y conocer el mismo entorno musical durante algunos años, hasta que en 1773 Palomino parte a Lisboa. La capital portuguesa representaba un importantísimo centro cultural, con una biblioteca musical famosa mundialmente desde mitad del siglo XVII y un gran desarrollo de la música de tecla, bajo influencia italiana, a lo largo del siglo XVIII. Junto a la música de corte real, abundaba la música de cámara y de salón, y no dejaban de llegar las novedades europeas, especialmente la música de Haydn.

José Palomino disfrutaba de un puesto acomodado como músico de la Real Capilla portuguesa, en un ambiente de modernidad y elegancia, y frecuentaba las academias particulares de la ciudad. En 1785 el conde Fernán Núñez, embajador de España en Portugal, le encarga Il retorno di Astrea in terra para celebrar el doble enlace matrimonial de los infantes de Portugal y España. Ese mismo año escribe el “Concerto o sia Quintetto per Cembalo o Piano Forte con due Violini, Violetta e Basso”, conservado en la Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal. Casi dos décadas posterior al Concierto de Narro, y mientras que en aquél la interacción entre tecla y cuerdas se limitaba al diálogo en alternancia, el Concierto de Palomino se asienta sobre un concepto camerístico en el que la cuerda, en la que cada línea adquiere un papel independiente, está más integrada con la tecla y juega con una construcción motívica entrelazada. De corte netamente clásico por estructura (allegro-andante-rondó) y lenguaje (bajo Alberti, frases sencillas, abundancia de apoyaturas y escalas, elemento sorpresa), el concierto desprende una elegancia, gracia y desenfado que nos recuerda a los primeros conciertos vieneses de W. A. Mozart, sin mayor pretensión, quizás, que la de entretener.

Los sucesos de las postrimerías del siglo XVIII ponen cabeza abajo esta burbuja cultural y musical. El fallecimiento de Carlos III en 1788 que precedió a la Revolución Francesa significó el fin del reformismo ilustrado, y la salida de la casa real portuguesa tras la invasión napoleónica, el final del absolutismo. En 1808, cuando João VI y la corte huyen a Brasil, José Palomino acepta el puesto de Maestro de Capilla en Las Palmas, donde se dedicó a reorganizar la pequeña orquesta del cabildo y a componer música religiosa hasta su muerte en 1810.

SOBRE LA (PRESENTE) GRABACIÓN

En febrero de 2015 La Tempestad presentaba en el Ciclo “Universo Barroco” del Auditorio Nacional de Madrid el reestreno en tiempos modernos y con criterios historicistas del Concierto para clave de M. Narro y del Concierto para dos claves de G. B. Pergolesi. Les acompañaban en el programa algunas de las Sonatas de Oposiciones a la Capilla Real de Madrid editadas por Judith Ortega, que en aquél momento nos recordó la existencia de otro concierto para clave hispano: el de José Palomino. Si el concierto de Narro recibió calurosos elogios, el de Pergolesi resultó ser la auténtica sorpresa de la noche y así lo transmitieron público y crítica.

Conscientes de la calidad de la música, vimos también la necesidad de mostrar y poner en valor un lenguaje muy diferente al que hasta ese momento representaban los conciertos para tecla de Bach, Haendel o coetáneos. Desde el brillo del temprano virtuosismo italiano –que tantísimos lazos cruzó con España y Portugal– al baile popular dieciochesco, el color del sur, los ecos de la guitarra rasgueada o la influencia de la escritura scarlattiana nos llevan a unos conciertos frescos, despreocupados, crujientes. Decidimos por tanto grabarlos. Hasta donde sabemos, este registro constituye la primera grabación mundial en CD de los conciertos de Narro y Pergolesi, así como la primera al clave del concierto de Palomino.

Porque es en este punto donde tocaba plantearse las primeras decisiones interpretativas: ¿para qué instrumento de tecla estaba escrito el concierto de Palomino? Pergolesi no deja opción a duda con el término “cembalo concertato”; tampoco Narro en su “Concierto de Clave”, más allá de la característica escritura clavecinística y de la ausencia de matices en la parte de tecla, y a pesar de que probablemente tuvo oportunidad de conocer los nuevos instrumentos –quizás, eso sí, después de la composición de su obra–. Si bien la publicación en 1578 de las “Obras de música para tecla, arpa o vihuela” de Antonio de Cabezón ilustraba una larga práctica común y una música menos atada al instrumento en sí, el Concierto de Palomino (invertimos el orden de las cifras y saltamos a 1785) se sitúa en un momento de evolución de los instrumentos de tecla en aras, precisamente, de una mayor expresividad. Lo cierto es que la entrada del fortepiano no fue súbita –entre otras razones por su elevado coste–, por lo que a menudo el clave seguía siendo el instrumento disponible. En el entorno de los hijos y alumnos de J. S. Bach, por ejemplo, la indicación “für das Clavier” dejaba la puerta abierta a los diversos instrumentos de tecla que convivían; C. P. E. Bach compuso su concierto en Mib Wq. 47 (1788) para clave y fortepiano; y en estas últimas décadas del siglo XVIII y primeros años del XIX los editores, conscientes del peligro, publican numerosas obras de tecla de Boccherini, Haydn o Beethoven indicando “para clave o fortepiano”. Esas mismas palabras aparecen en el manuscrito de Palomino –con lo cual en este caso no es táctica editorial–. Ciertamente su escritura se adapta perfectamente a la sonoridad del fortepiano; la corte portuguesa fue uno de los primeros lugares donde se comenzó a escuchar el nuevo instrumento; y el rey João V financiaba su construcción al tiempo que enviaba al extranjero aprendices portugueses. En fin, la practicidad –es más difícil encontrar fortepianos hoy en día que probablemente en el entorno de Palomino– y el hecho de que ya existiera una grabación al fortepiano nos hizo inclinarnos por la versión al clave.

Sorprende a primera vista que Narro prescinda de la parte de clave en su segundo movimiento. Tampoco hay rastros de cifrado, y no parece probable que el autor dejara al intérprete la libertad de improvisar sobre el movimiento según el hábito barroco: frente a la construcción armónica que podemos encontrar en los movimientos lentos de un concierto de órgano de Haendel, por ejemplo, Narro mira adelante en este Andante de corte clásico: el material temático perfectamente dibujado en las líneas de los violines encuentra respuestas elegantemente hiladas en los bajos. El lenguaje galante muestra así un frágil y bello equilibrio de la cuerda frotada que se quebraba rápidamente a la entrada de un plectro. No así en Pergolesi, donde el lirismo y el cantabile de los dos claves cobran un protagonismo un punto meloso para el primer tercio del siglo (y que a nuestro entender alimenta la duda de la autoría).

Otros aspectos a decidir incluían el uso de un segundo instrumento de tecla en el papel del bajo continuo y la realización –o no– de cadencias. Optamos por sumar el bajo continuo al concierto de Narro para crear un segundo plano con el acompañamiento de clave integrado en la orquesta, frente al clave solista; y pensamos que en Palomino, más alejado de la sonoridad barroca, era preferible sacrificar el acompañamiento para ofrecer un color más camerístico y cristalino. La práctica de improvisar cadencias –como indica la musicóloga María Gembero– no era una cuestión universal: frente a la costumbre germánica (C. P. E. Bach dejó escritas un gran número de ellas), las cadenzas faltaban casi siempre en los conciertos parisinos del Clasicismo y es una práctica todavía sin documentar en la Península Ibérica: Narro no señala dónde deben realizarse y los calderones en Palomino (además de ser demasiados) no se corresponden con los lugares armónicos habituales para una cadencia, sino que más bien insinúan una breve pausa antes de retomar el rondó.

Por último, la edición de la partitura del Concierto de Narro llevada a cabo por María Gembero incluye un interesante y completo estudio y nos resultó esencial para el trabajo previo. Sin embargo, creímos conveniente realizar una edición práctica de partitura y partes tanto de la obra de Narro como del concierto de Palomino. Es lo que hicimos a partir del manuscrito facilitado por la Real Colegiata de Roncesvalles –en el primer caso– y del manuscrito autógrafo conservado en la Biblioteca Nacional de Lisboa –en el caso de Palomino–.

Punto y final. Estamos seguros de que estos primeros conciertos ibéricos cumplieron su función de divertir a un público probablemente reducido, quizás mientras sonaban los cascos de los caballos en las losas del patio y con el eco de las castañuelas al fondo. Volviendo al punto de partida, y haciendo propias las palabras de Isla, dejemos ya juzgar al público, “poderosísimo señor:”

Desengañémonos: sólo usted tiene este gran poder, porque sólo usted en este particular (hablo de tejas abajo) puede todo cuanto quiere. Quiera el público que nadie chiste contra una obra; nadie chistará. Quiera el público que todos la celebren interior y exteriormente; todos la celebrarán. Quiera el público que se reimprima mil veces; mil veces se reimprimirá. Y este poder no es limitado a estos o aquellos dominios; extiéndese por donde se extienden los dilatados ámbitos del mundo. En cualquiera parte donde hay hombres hay público, porque el público son todos los hombres.

Silvia Márquez Chulilla