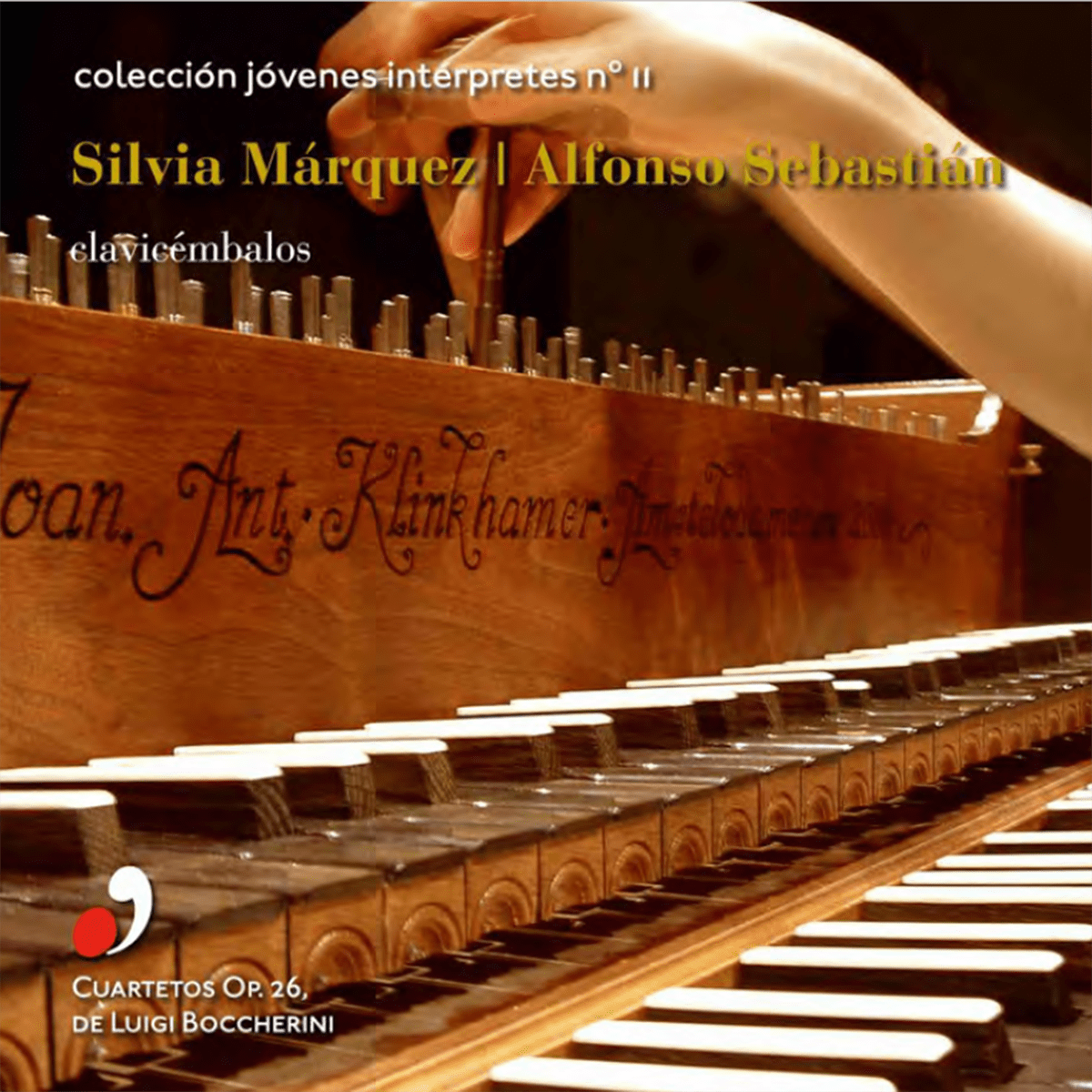

LUIGI BOCCHERINI

OP QUARTETS. 26

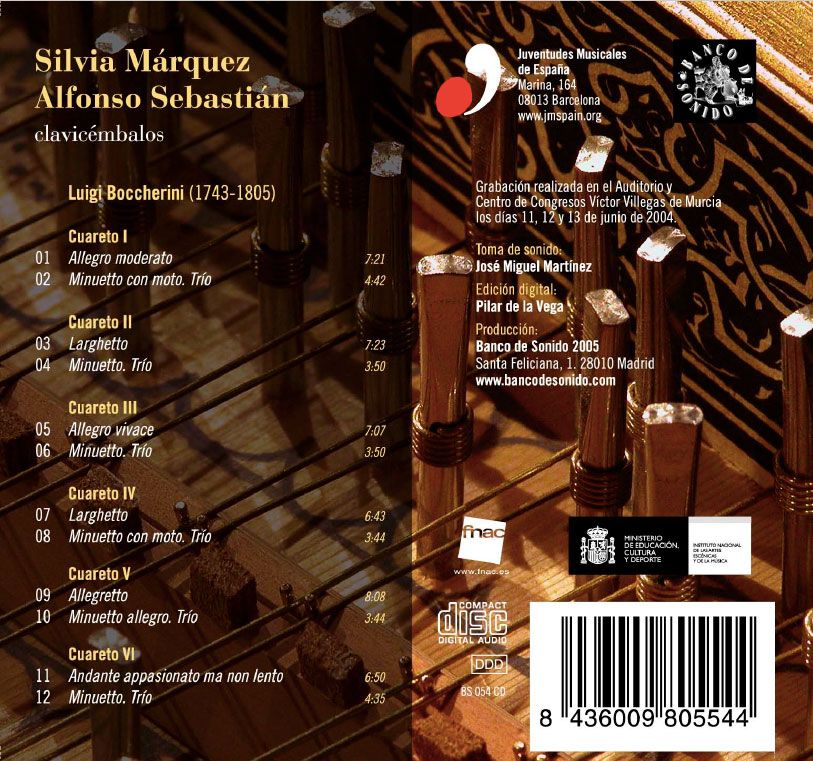

SILVIA MÁRQUEZ CHULILLA & ALFONSO SEBASTIÁN, clavicémbalos

COLECCIÓN JJMM N.º 11 BS 054 2005 | DL M-30197-2005

Despite the rich surrounding environment, Luigi Boccherini devoted little attention to the key. Luckily, his music was known throughout Europe and there was no lack of hands ready to enjoy it with the most common keyboard instruments. This is the case of the Cuartetos Op. 26 , composed in 1778 – in that position accommodated to the service of the Infant that allowed him to devote himself completely to his creative activity – and published in Vienna in 1781 by Artaria as Op .32.

Here is a version for two keys – from a manuscript of the Sächsische Landesbibliothek of Dresden – in the hands of the winners of the Key Contest of Musical Youths of Spain in its edition of 1996.

SOLD OUT

CD CONTENT

Cuarteto I

01. Allegro moderato

02. Minuetto con moto. Trío

Cuarteto II

03. Larghetto

04. Minuetto. Trío

Cuarteto III

05. Allegro vivace

06. Minuetto. Trío

Cuarteto IV

07. Larghetto

08. Minuetto con moto. Trío

Cuarteto V

09. Allegretto

10. Minuetto allegro. Trío

Cuarteto VI

11. Andante appasionato ma non lento

12. Minuetto. Trío

CD NOTES

THE TRANSCRIPTION IN THE XVIII CENTURY

The quartets op. 26 by L. Boccherini

Bien into the 18th century, the rich existing production originally written for two keys or four hands demonstrates the popularity of this practice, to which pages such as F. Couperin, G. le Roux, A. Soler, J. S. Bach, W. F. Bach, J. Bach, J. . L. Krebs and J. G. Turk, among others. To this we must add the incessant custom of transcribing pieces for various instruments from their original version to key or two keys and vice versa: just remember the masterful transcriptions for key that J. S. Bach performed from the concerts of Marcello or Vivaldi, C. Ph. E. Bach’s own transcription of his Concerto in B flat major for key and orchestra (Wq. 25) to two keys, and j. G. Naumann’s concert, “accomodato per due cembali”, an Italian term of great acceptance in European music from the eighteenth to when it comes to transcribing quartets or concertos for soloist and orchestra. At the end of Le Rossignol en amour, from the XIV Ordre by Francois Couperin, the following indication appears: “This piece can be played with different instruments. Even to two keys or spinels, namely the subject with the bass in one, and the same bass with the counter-subject in the other; like the other pieces that can be found as a trio.”

Orbvia, all this music flow between composers, countries and instruments depended on the occasional circumstances, the available instruments and, in many cases, commercial interests. The fact that in 1784 the Journal of Parismentioned as “still very new thing” a four-hand performance by Sejan and Charpentier is explained in a very simple way: the transcriptions allowed to enjoy chamber or orchestral music in from concert halls to the domestic sphere. For this reason, there are not abounding, the references written in treaties, press estiquetions or encyclopedias of the time, but it was a widely extended practice: “This Trio, like the Apotheosis of Corelli and the complete Book of Trios that I intend to publish next July, was can interpret two keys, as well as on any other instrument. I play them with my family and my students, with an excellent result (…). The truth is that this forces you to have two copies instead of one, and two keys as well. But I think it’s easier to find these two instruments than four professional musicians (…)”. (F. Couperin in the preface to the Concert instrumental sous le titre d’Apothéose… Lully). The publishers knew this, and in the titles of the works they published offered alternatives not to limit sales: they appeared interchangeably oboe/flute or key/fortepiano, recommended the performance with other instruments or even dared to fix symphonys for small chamber groups, as Salomon did with J. Haydn’s London symphonies (which he arranged for trio and later for string quartet with flute and fortepiano).

Cuartetos and quintets form precisely the central core of the work of Luigi Boccherini (1743-1805), a cellist and composer who had already collected hits in Milan, Vienna, Rome and Paris upon his arrival in Spain, and had formed the first quartet for a paying audience (with works by Haydn, Nardini and himself). In the spring of 1768, following the advice of the Spanish ambassador in Paris, he set out on a trip to Madrid, where numerous Italians (Scarlatti, Farinelli, Sachetti, Brunetti, Conforto, Corselli…) enjoyed excellent consideration. He writes music incessantly hoping to win the favor of Prince Charles, in vain. Finally, a Royal Decree of 1770 in Aranjuez appoints him chamber celloon and music composer of the infante Don Luis de Borbón.

Comwill frantically set quintets, quartets, concertos, sonatas… that will open new horizons to camera instrumental music. It is a pity that Boccherini, although he did fix his music for instrumental formations other than the originalons, did not at any time follow the habit of transcribing it for key or two keys. In fact, he devoted little attention to this instrument, and did not even write a work for key alone or for organ, a surprising circumstance considering the closeness of D. Scarlatti and the important collection of key instruments that the Court had, as well like the fantastic organs I had at my fingertips in illustrated Madrid. Luckily, his music was known throughout Europe (the publishers of Paris promised to make his famous work and got it, in addition to enriching himself at his coast), and there was no shortage of hands willing to enjoy it with the most common key instruments. This is the case of the Op. 26 Quartets, composed in 1778, in that position accommodating the service of the Infante that allowed him to devote himself entirely to his creative activity, and published in Vienna in 1781 by Artaria, as Op.32.

Hoy we present a version for two keys found in a manuscript of the Dresden S.chsische Landesbibliothekde. The date and the author are unknown, but he had to be undoubtedly a very skilled musician or amateur or a harpsichordist with a long time to expand the repertoire, for from the same hand there is also another transcription of these quartets for key and string, and more arrangements for two keys. Faithful portrait of the original of the Quartets, the transcription, as we have seen in F. Couperin’s explanations, distributes the parts as follows: cello for the left hand of the first key and violin first for the right hand; viola for the left hand of the second key and second violin for the right hand. The only freedoms allowed by the transcription are small variations in the typical cello writing of repeated notes in semi-corks, which in the key become brackets (and which have justification in the timbral homogeneity of this instrument, which would easily produce too many accents on each of those notes.) We, moreover, have added some chord or arpeggio to create crescendo effects that would otherwise be impossible to achieve (following the usual practice of the harpsichordists of the time, accustomed to using these resources from their part of basso continuous).

En Boccherini’s catalogue these Op Quartets. 26 appear as ‘opera piccola’ , qualification which he himself grants to works of small dimensions and in two movements, as opposed to that of ‘opera grande’, of three or four Movements. In editorial terms, this distinction also had an economic implication: the former were cheaper.

Rrestricted to two movements, brevity forces him to sharpen the ingenuity to present varied and contrasting themes in miniature, and he does so within the formal framework of the sonata for the first movements and the minuet for the final movements. As Yves Gérard has emphasized, the achievement is to present in each initial movement of the quartets an expressive aspect of the sonata: no 1, a certain Italian style of writing; 2, the pre-classical style; the no. 3, brighter and symphonic, and in E flat major (Boccherini’s favorite tonality), contrasts with the repetitive grace of the Larghetto of No. 4; the number 5 is the closest to the classical sonata form; and at No. 6 the “romantic vein” of Boccherini looms.

Inteligente combination for a set of 6 pieces in which the effort to vary does not cease, intensified by the final minuets that, contrasting or not, show all of them influences of Spanish music: guitar writing (no. 2), dances, harmonies taken from folklore (no. 6), from the street…

No was at all a new language for him: he had already introduced in previous works dances such as fandango or popular themes such as folía. Boccherini’s chamber music does not support adjectives of the type therist, heavier, afflicted, heartbreaking, painful… It is a joyful, festive, optimistic music, written to the taste of the Court and Infante Don Luis, from a comfortable situation, of fertile and happy years, and without obligations. Boccherini, permanently installed in Spain, works here but without losing contact with the outside world, where his works circulated handwritten or published by the best editors of the moment. It is no wonder that in 1785 Crown Prince William Frederick of Prussia appointed him his chamber composer. Nor was he oblivious to the novelties of European composers. If he did not follow the currents to use it was because he did not want: because he remained faithful to his style and spirit.

Italy, paradoxically, had given us the “most Spanish” composer of chamber music in 18th-century Europe.

Silvia Márquez Chulilla