FIVE NEW PIECES

RODERIK DE MAN

ANNELIE DE MAN & SILVIA MÁRQUEZ CHULILLA, claves | VARIOS

ATTACCA BABEL 1999 | 9989

Formado en sus inicios como percusionista, Roderik de Man fue Profesor de Composición en el Real Conservatorio de La Haya entre 1972 y 2008. En su obra destaca la búsqueda de formas orgánicas y el ritmo, el “poder más vital” de la música.

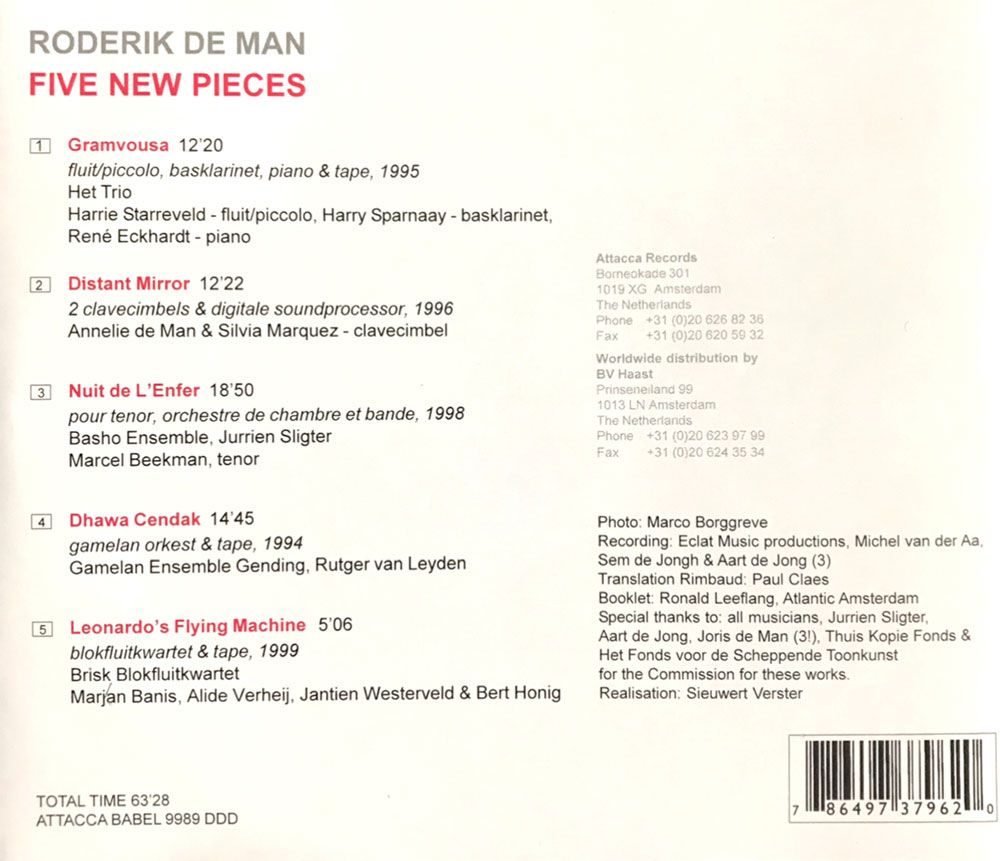

En Distant Mirror subyace, junto a todo ello, la música antigua: la famosa fantasía cromática de Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck. No es una cita literal, sino que mediante dos claves y una pequeña configuración de electrónica en vivo, Roderik muestra la fantasía de Sweelinck reflejada en un espejo distante. Desde lejos, se escuchan vagamente fragmentos de la música antigua que se unen para construir algo nuevo.

CONTENIDO DEL CD

Five new pieces

Gramvousa (1995)

para flauta/piccolo, clarinete bajo, piano y tape

Het Trio:

Harrie Starreveld, flauta/piccolo

Harry Sparnaay, clarinete bajo

René Eckhardt, piano

Distant Mirror (1996)

para 2 clavicémbalos y procesador de sonido digital

Annelie de Man &

Silvia Marquez, clavicémbalos

Nuit de L’Enfer (1998)

pour tenor, orchestre de chambre et bande

Basho Ensemble

Jurrien Sligter, flauta/director

Marcel Beekman, tenor

Dhawa Cendak (1994)

para orquesta de gamelán y tape

Gamelan Ensemble Gending

Rutger van Leyden, director

Leonardo’s Flying Machine (1999)

para cuarteto de flautas de pico y tape

Brisk Blokfluitkwartet

Marjan Banis, Alide Verheij,

Jantien Westeveld & Bert Honig, flautas de pico

NOTAS AL CD

Every piece is a journey with new vistas

“Of course, I’m not really objective with regard to my own music, but if I try to formulate a sort of credo, I would choose organic contrast, “ says Roderik de Man (1941). “I didn’t think of that myself. Thea Derks used those words to describe the core of my work in a brochure of my publisher Donemus.”

“I’m strongly focussed on the architectonic form of a piece. Abstract structure fascinates me, to me music is a kind of unconscious mathematics. Proportions should be right and developments should have a logic, but at the same time be able to surprise the listener. I try to create organic forms, mostly based on only a limited amount of intervals from wich I build different motives, related to each other like in a family.”

“In general, my works are not very lengthy. I like concentrated forms that don’t give away all of their secrets at once. In line with that, most of my music is built in several counterpointing layers sounding at the same time. I started out as a percussion player, and I think that too shows in my work as a composer. To me rhythm is the most vital power in music, and although there are electronic parts in my work quite often, I will therefore never write these in a purely colouristic way in which there is no definite pulse anymore. I’m very much attached to a rhythmic heartbeat.”

“Usually I start with drawing a sort of map of the piece I’m going to make. It’s very possible to make a graphic representation of what is going to happen in the work. In this sketch I could, for instance, write down a succession of intervals construct a given passage. I do not consider this to be relevant to the listener. Important is only that I can create a coherence in the music, which the audience will experience subconsciously without knowing exactly how it is all put together. The same applies to the proportions within the piece. I know how they’re right and the listener will experience that they’re right without knowing why. I need this sketching process just to five a direction to my ideas. As soon as the work is finished these little maps are just as unimportant to me as to the audience. I always throw them away.”

“To me each new work is a new journey with new and unexpected vistas and this means that I don’t work in strict preconceived systems like in for instance serial music. There has to be control, but it shouldn’t become so rigid that I couldn’t give a blow on an anvil if I want to. You could say that I work systematically without starting out from a system. It is always a matter of intuition and ratio and every piece demands to find this balance in a different way.”

“In Nuit de l’Enfer, I write different melodic lines than in Dhawa Cendak which is made for the Gamelan ensemble Gending. Due to the instrumentation in l’Enfer, the lines are longer and rhythmically less proliferated. The one piece is for chamber orchestra and voice and the other for a percussion ensemble that hasn’t got the possibility to produce long sustained sounds. On top of that, the dramatic text by Rimbaud used in l’Enfer asks for a grand gesture. What he writes is almost hysteric and I made a sort opera scene out of that.”

“Also the use of electronics is quite different in those two pieces. In l’Enfer, I made interludes on tape in which you can hear the poisoned drink referred to in the text. Dhawa Cendak means ‘long – short’ and that is what the piece is about. You cannot make long sustained sounds on a gamelan because for the most part the ensemble consists of bronze instruments the sound that decay rapidly. The beautiful rich sound of these gongs however, is very well adapted to electronic manipulation. I made samples of different instruments and reworked them in such a way that I got long sustained sounds. On the tape, I could transform short sounds into long ones, and that is the process underlying the piece. The basic idea of this tape is very different – more abstract, architectonic – from what happens in l’Enfer, where the electronic part is much more an expressive theatrical addition to the orchestral part.”

“It’s a coincidence that there is an electronic element in all of the pieces on this CD, but it is true that I often write for a combination of instrumental and electronic means. Partly, this is caused by the simple fact that I’m adked for pieces like this – I write almost everything on commission – but of course i’m also fascinated by the extra possibilities the use of electronics offer. You can really make your own sound palette and you can expand on the possibilities of the instruments. If you write for a small ensemble, you can still think in a symphonic way if you add a tape.”

“In general, I use electronics only as an addition. The electronic and the instrumental parts are always equally balanced and I always try to preserve an instrumental breath in my tape parts. Because I’m attached to this instrumental quality, I often use samples of instruments as the basis for the tape. It’s fascinating to be able to put instrumental sounds under the microscope of electronics and build new related sounds from a detail. In the sound of a violin for instance, there is a lot of high white noise that you don’t really perceive when you hear the instrument. If I take a sample of a violin tone, I can manipulate that in such a way that it will put the white noise to the fore. It is only an example, but it illustrates how you can create a clear relation between electronics and instruments.”

“In the piece for Het Trio – Gramvousa – I enlarged the air with which the flute is blown in a similar way. I asked their flute player Harrie Starreveld to produce sounds with as much false air as possible, recorded those, and started from there for the tape part.”

“In this piece the wind has an important part to play. Gramvousa is a small isle in the Mediterranean sea, close to Crete. This island is referred to in Homer’s Odyssee. In Homer’s tale Aeolos , the Greek God of the winds, lives on Gramvousa and it is also Ulysses’ starting point for the long dangerous journey to his homeland Ithaca. I’ve been to Gramvousa and there you discover that it made sense to the Greeks to see this isle as the home of Aeolos. On a clear and quiet day there can suddenly appear strong brakes of wind, that lay down just as quickly as the came.”

“When I got the commission for the piece, I had to think of Ulysses’ journey. To a composer the writing of a piece is also a journey with an uncertain destination. The winds of Gramvousa matched the line up of Het Trio very well: a piano and two woodwinds – flute and bassclarinet. The tape is almost completely built on manipulated sounds of the instruments. I tried to bend the sounds of the instruments towards each other. I manipulated arpeggios on the piano in such a way that they almost blend with the sound of the bassclarinet.”

“Leonardo’s Flying Machine was commissioned by the recorder quertet Brisk. To commemorate the millennium change they asked a number of composers to write a piece with exactly 2000 notes. I didn’t know what to make of that, so I came up with something else. The title referes to the sketches Leonardo da Vinci made for a number of flying machines. In stead of writing those 2000 notes, I chose to write a piece that gave the Brisk quartet a trascendental medium of transport for at least 20.000 miles into the next millennium.”

“It is in a sense again a journey, be it now in one of Leonardo’s flying machines. You can hear the flapping of it’s wings on the tape. Like a Gerauschmacher who took care of the soundtrack in old silent movies or in radio plays I shook a pillowcase in order to get this sound. I recorded it slowed down the sound on the tape. During the flight you hear a short quote from a piece by the renaissance composer Josquin Desprez. Besides new music Brisk plays a lot of old music and Josquin’s was scheduled after mine in the programme in which it was premiered. You hear Josquin from above in Leonardo’s flying machine.”

“Such a perspectivic insight from the present into older music is also there in Distant Mirror. In this case, the old music is Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck’s famous Chromatic Fantasy. The original is for organ. My piece is for two cembalo’s and a small set up of live electronics. I didn’t cite Sweelinck’s work literally in this case. I used his material – intervals and a short, characteristic phrase – to make a piece that shows Sweelinck’s Fantasy as if reflected in a distant mirror. From afar, you can vaguely hear bits and pieces of the old music that are put together to build something new in which the past is still preserved.”

Roeland Hazendonk