TUMULO CANORO

PERE ROS & SABINA COLONNA, violas da gamba - EDUARDO EGÜEZ, laúd y tiorba | SILVIA MÁRQUEZ CHULILLA, clave

ARSIS 4216 2008 | DL HU 386/2008

The exquisite recording of the Arsis label reflects on a single invariable space: the duel as a visual and sound landscape.

If the baroque composers always tried to affirm their willingness to move the affections of the listeners, in a few genres they achieved it more effectively than in that of the lament. It is following the spirit of the tombeau that this album has been composed around works for viola due to F. Couperin and Marin and Roland Marais, which are completed with a beautiful zarabanda for the key of William Babell and an allemande for the lute of WJ Lauffensteiner, both also identified with the name of tombeau .

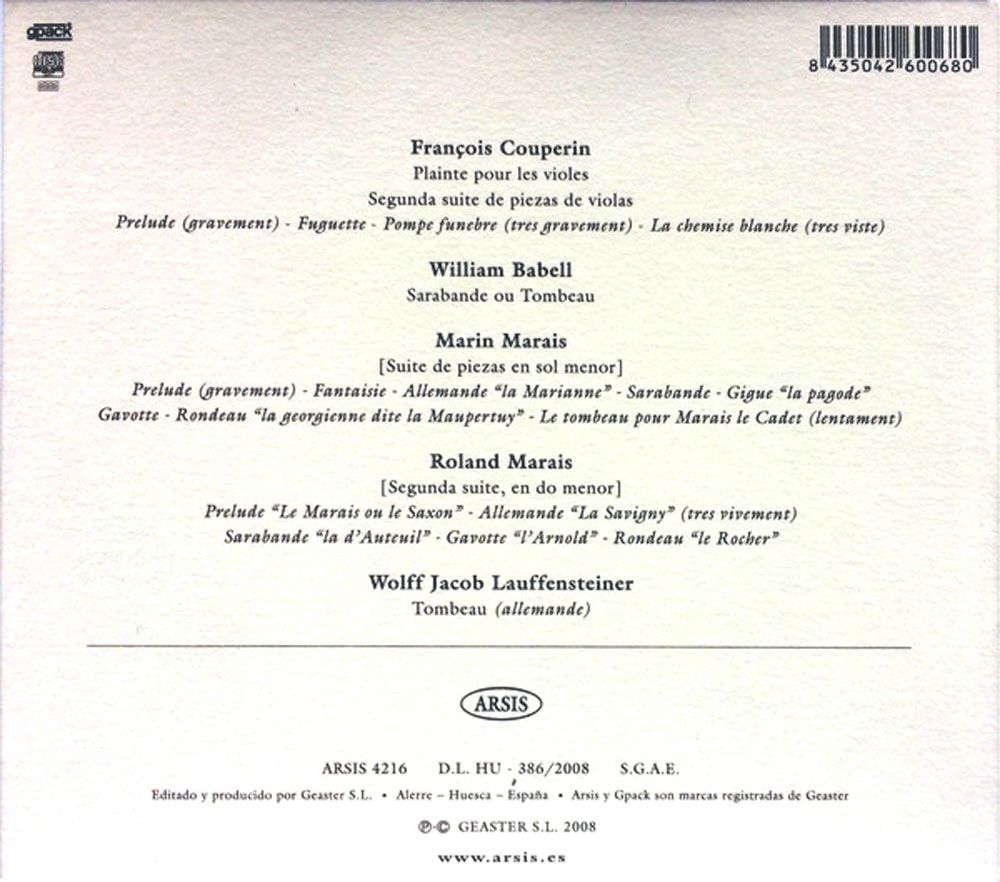

CD CONTENT

01. Plainte pour les violes

Segunda suite de piezas de violas:

02. Prelude (gravement)

03. Fuguette

04. Pompe funebre (tres gravement)

05. La chemise blanche (tres viste)

William Babell (1690-1723):

06. Sarabande ou Tombeau

Marin Marais (1678-1741):

Suite de piezas en Sol menor:

07. Prelude

08. Fantaisie

09. Allemande “la Marianne”

10. Sarabande

11. Gigue “la pagode”

12. Gavotte

13. Rondeau “la georgienne dite la Maupertuy”

14. Le tombeau pour Marais le Cadet (lentament)

Roland Marais (1680-1750):

Segunda suite, en Do menor:

15. Prelude “Le Marais ou le Saxon”

16. Allemande “La Savigny” (tres vivement)

17. Sarabande “la d’Auteuil”

18. Gavotte “l’Arnold”

19. Rondeau “le Rocher”

Wolff Jacob Lauffensteiner:

20. Tombeau (Allemande):

CD NOTES

Piadoso hoy celo, culto

cincel hecho de artífice elegante,

de mármol expirante

un generoso anima y otro bulto,

aquí donde entre jaspes y entre oro

tálamo es mudo, túmulo canoro.

Luis de Góngora y Argote, in the tomb of Garcilaso de la Vega

From tombeau as allegory and landscape

Musical space is undoubtedly the opposite of a a priori: the elements that articulate it must, for a sudden, be produced to be audible, taking on shape and contours as they appear in the there that they determine, what they confers – as with every work of art – an eventful character.

Three heterogeneities are the vectors of their spatialization: one or more series of harmonic relationships whose object is such or which concurrency; one or more series of melodic evolutions in which what counts is, on the other hand, succession; and, finally, one or more sets of rhythmic patterns that ten and dissect such series by establishing mobile connections between them.

Such is, in broad terms, the logic inherent in the musical space, whose organization elicits a certain number of animus affections that not only fill it, but add a new dimension in which that space is unfolded, a dimension that can and must nevertheless , wanting to be oriented with a view to the selection of the logical criteria capable of transforming the passions of the soul, which is always discussed in the Baroque, into a specifically musical piece. And just as it would be insufficient to remain on that last level, affective or moral, regardless of the logical or formal scope whose elements he informs and amplifies, it would also be absurd to ignore the fact that a second space thus adds up in this way, in a strong sense, to the first. Musical space is, in short, a forked space.

Inseparable from each other, such dimensions nevertheless form an even incomplete whole, since there is a third area – or a second unfolding – to consider here, namely: that of musical space as an individual body by the effect of the combination of certain formal and affective values. We will call the latter – which is which we will deal with above all in these lines – the landscape or physical space of music, which is imposed on an essentially descriptive look even without no longer wanting itself, in another sense, listens. It is, in fact, a landscape that conveys to the listener the affections of the soul transformed at a time in sounds and images. It therefore corresponds to this space an interstitial or frontier quality, ambivalent and, therefore, paradoxical, because we say both that its images can be heard and that their sounds are representative, and one depending on the other.

The recording to which these lines accompany must be seen, according to this, with the multiple figurations of a single invariable space: that of bereavement as a visual and sound landscape capable of adopting plural traits by virtue of the same rule applied here and there. Whether it’s the descending series of four or more notes, the vibrant repetition of others as a squeak or its arrangement in the form of a swell… All these cases – to which others could, of course, be added – highlight the same procedure consisting in the formulation of a particular analogy: the tilt-lament, the funeral ringing of a bell or the swing of the overt crying. And it’s that way that duel charges, at the same time, sound and figure.

However, the analogy is not only one more resource within the limits of that space, but, strictly, the fundamental law that establishes it and distributes its contents. Now, what exactly is its scope? Let us look blankly: it is not a question of rediscovering, in depth or on the surface, such or which symbols to which she would refer linking the particular to the universal, the singular to the generic. The given does not refer here to anything else but on the condition of incorporating it into the theatre of the world: by staging it, it embodies the idea and exposes it to the future. The analogy thus makes a allegorical sense rather than symbolic, just as we add – in the tombeau as the Baroque’s own art.

Each of the above-mentioned motifs is the axis around which one or more of the pieces collected in this CD revolve. But not only do such reasons differ from one piece to another, but also the horizon on whose margins the mourning as a landscape, which may be loved bright or dark, unsettled or calm, differs in them. And, therefore, the accent and temperament of each work regarding what they evoke in particular: the memory of the cented person, the expression of pain at his death or the procession that accompanies the deceased, for example. But when we talk about the accent of each one we could also do it the type of stroke to which, as figurations of a certain space, they respond.

Thus, in his Sarabande ou Tombeau in D major (1702), William Babell bestows on evocation, it would be said, a form of sereno remembrance: a series of delicate brushstrokes, more courteous than passionate but certainly melancholy, and repetitive, seem to recall the Absent. In contrast, Wolff Jacob Lauffensteiner adopts a more serious and solemn tone – elegiac, we might say – in his Tombeau (ca. 1710) in C minor, a key to which M.-A.J. Mathesson will emphasize shortly thereafter (cf. its Das Neu-Eroeffnete Orchestre, Hamburg, 1713) which “easily moves to drowsiness” and which is ultimately suitable for expressing “bereavement or feeling of lack”. The harpsichord and the lute somehow take hold of that contrast: the satin and ethereal timbre of the former differs from the wet and velvety timbre of the second.

But absence moves the cry, and crying – unnecessary, it is said – flows; flowing that evokes, in turn, unbeatablely, the viola da gamba, an arc instrument, and no longer a pulsed string, whose genealogy shares sections, however, with the lute (arc vihuela, was called in Spain, it should be remembered, during the Renaissance). It is precisely served by Marin Marais in his Tombeau pour Marais le cadet in G minor (ca. 1725) and Francois Couperin in his Plainte pour les violes ou d’autres instruments é l’unisson and in his Pompe fun., both in the major.

A new contrast appears here, for while in its Plainte pour les violes… Coupein monotonously prolongs the lament, from which several voices participate in unison and which is no longer narrative in character – unlike what we saw before – and this to the beat of the tañer of a “bell” whose sound would be said to suspend the time at the rate at which it advances the funeral procession or announcing the office of the deceased – unison that at times gives way to the counterpoint, which makes crying as natural as desolate – Marais presents to us the lament moved by the death of one of his sons as a repeated sigh , loving and paternal that, sometimes torn – certain blows of the bow give in evoke, in its own way, the melismatic style of singing – ends up placating and resigning itself to start again, like a breath overwhelmed. And both works contrast, in turn, with the majestic Pompe fun-bre of Couperin himself (published, curiously, the year of Marais’s death: 1728), which covers a more rhetorical and elaborate discursive form, but equally poaperish.

This short journey, of course, is far from being exhaustive, since it is not the intention of these lines to reduce the works commented to the aspects mentioned herein or examine one by one all those contained in this CD. But if he has served to provide the listener with some of the concepts and impressions that flow from the exciting aesthetic-musical universe of the tombeaux, there will be – let’s hope for it – it was worth it.

Carlos A. Segovia